By Natasha Rausch

Editor’s note: This is the third installment of a three-part series on the crisis of missing and murdered Indigenous women in the upper Plains.

Half a dozen Native and non-Native women alike sat around a table in the lobby of the Plains Art Museum for their monthly meeting on missing and murdered Indigenous people, or MMIP. Their group was formed shortly after a local Native American woman, Savanna LaFontaine-Greywind, was brutally murdered in August 2017. The members of the group, known as the Fargo Missing and Murdered Indigenous People Task Force, have a shared trauma, said Ruth Buffalo, a member of the Mandan Hidatsa Arikara Nation and a Democratic state representative for Fargo.

They all joined in the search for LaFontaine-Greywind, whose body was found by kayakers along the Red River nine days after she disappeared. The river, which runs from southern North Dakota into Canada, has been the dumping site of hundreds of Indigenous people’s bodies over the years, according to the Sovereign Bodies Institute, a group working to document such cases in North America.

LaFontaine-Greywind was murdered, and her baby was cut from her womb. The child survived despite the violent ordeal. And the case sparked international outcry and even a bill in Congress that has yet to pass.

After LaFontaine-Greywind’s death, Buffalo helped form the local task force and a handful of women joined in the effort. Now, they help out with the annual MMIP March on Feb. 14, an event started locally by the awareness group Sing Our Rivers Red. They use their Facebook page to provide resources and raise awareness when people go missing. They set up booths at local events, and they organize viewings of relevant documentaries and artwork.

“We have to be more proactive,” Buffalo said. “And oftentimes, it takes a horrific thing for people to take action.”

They’re not the only ones taking action, though. Grassroots movements are popping up across the Plains in the form of organizations, civilian search crews, and awareness walks and rallies.

One local artist created a piece to start conversations about the crisis of missing and murdered Indigenous people. One group of activists walked 550 miles along the Red River from Wahpeton, N.D., to Lake Winnipeg, Canada, to pray for the water and the Indigenous people who have been dumped in it. One group of horseback riders traveled 200 miles from Santee, Neb., to South Dakota’s capital city to honor missing and murdered women. One Indigenous designer has modeled entire fashion shows to raise awareness of missing aunties, moms, daughters and sisters. One North Dakota woman has dedicated her life to searching for missing and murdered Indigenous people.

And hundreds of people have gathered to march in rallies and look for missing people as families across the Plains struggle with no answers when their loved ones go missing.

“This is a spiritually motivated movement,” said searcher Lissa Yellow Bird-Chase.

murdered Indigenous people across the country. Natasha Rausch / The Forum

Yellow Bird-Chase, 51, gave up her Fargo career as a welder to become a full-time searcher for what she calls the crisis of missing and murdered Indigenous relatives. “Every generation almost is missing a relative,” she said.

Even the license plate on her black SUV reads “SEARCH.”

Yellow Bird-Chase, a member of the Mandan Hidatsa Arikara Nation on the Fort Berthold Reservation, started searching for missing people almost a decade ago. She’s since created the Sahnish Scouts of North Dakota, a handful of people who help her search, and she’s worked on cases across the country, from the Dakotas, Montana and Minnesota to Iowa, Oklahoma and Nebraska, all the way to California.

She quit her job in Fargo, spent her retirement savings and the money made from selling her house – all in the name of searching for the missing.

“If there’s someone out there missing, I’ll do whatever I have to to find them,” she said.

She’s a self-taught sleuth. And she’s tough. “I live, breathe and sing missing and murdered,” she said.

Olivia Lone Bear went missing on the Fort Berthold Reservation in the fall of 2017. The following summer, Yellow Bird-Chase took her boat, equipped with sonar, onto Lake Sakakawea. A young, hopeful searcher, who tagged along, watched the sonar and located the truck Lone Bear was last seen in underwater. Once pulled from the water, Lone Bear was found in the vehicle.

Yellow Bird-Chase also helped in the search for Savanna LaFontaine-Greywind, and in the search for Melissa Eagleshield, who went missing near Detroit Lakes, Minn., in 2014.

Besides looking on her own, she trains new searchers. From that, she said half a dozen other search crews have sprouted. Over the years, she’s gotten new resources for the Sahnish Scouts, too. Besides a boat and sonar, the crew now has access to a dozen dogs that can detect human remains, and soon she’ll learn how to use ground-penetrating radar.

Yellow Bird-Chase’s family wanted her to stop searching for missing people a long time ago, though. Her mom said it’s a drain on her. But she’s independent, determined.

For Yellow Bird-Chase, the hardest part isn’t the searching. It’s watching the families devastated by the loss of their loved ones go into “dark places,” she said. “Do you know how heartbreaking it is to watch families go through that?”

Sixty-two-year-old Rose Grusing of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe in South Dakota has been in that dark place for 16 years.

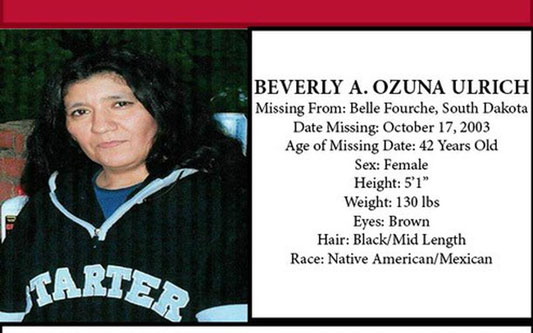

Her younger sister Beverly Ozuna Ulrich went missing on Oct. 17, 2003, and hasn’t been heard from since.

Grusing has long lived in Belle Fourche, S.D., just northwest of Rapid City. Her sister also lived in the town before she went missing. In the 16 years since Beverly was last seen, Grusing lost three of her brothers, and two sisters, too. Before that, she lost her mom, and another brother and sister to cancer. Now she and her oldest brother are the only two left.

Grusing has long thought about leaving town, starting over. But she can’t. “I can’t leave her,” she said of her missing sister. “I’d be abandoning her.”

As the youngest girl, Beverly was the most spoiled growing up, Grusing said. And she was easygoing, like her mom, too. Grusing said after their parents’ divorce, their mother started heavily drinking alcohol, and eventually, the kids were split up into foster homes. Beverly, she said, was traumatized by her foster home experience.

Two of Beverly’s daughters, Stevie and Katrina, continue to update a Facebook page made for their missing mother. “It’s another year without Mom,” her daughter Stevie posted on what would have been her 69th birthday this year. “Just know we will never give up until we have you home and justice for you!”

Once the family realized Beverly was missing, they tried figuring out where she was on their own, Grusing said. A few days later, they reported her missing to law enforcement. Butte County Sheriff Fred Lamphere said Beverly was last seen in the nearby town of Spearfish before a friend brought her back to Belle Fourche. He estimated law enforcement has conducted seven or eight separate searches since Beverly went missing.

“We don’t really have a crime scene. We don’t have a location someone went missing from,” he said. It’s now considered a cold case.

Lamphere said foul play is suspected in her disappearance and that law enforcement has a “very strong suspect.” There’s just not enough evidence to charge the person. The sheriff said his office is always open to any new leads or evidence.

After 16 years, Grusing said she’s lost faith in investigators. She’s often called on psychics or medicine men to help look for her sister and even ventured out to search with other family members. “It makes you crazy because you don’t know what happened,” Grusing said.

Besides searching, Grusing helps organize an annual candlelight vigil in remembrance of Beverly each year at the First Congregational Church in Belle Fourche. And she tries to get the word out, telling her sister’s story.

“I don’t want people to forget her,” she said.

Not knowing for 16 years has been the hardest part, Grusing said. She still thinks about Beverly every day, all day. “I even still have that little tiny glimmer of hope, that she’ll show up at my door.”

If you or someone you know is a victim of violence, please consider calling the National Indian Women Resource Center at 406-477-3896 or the StrongHearts Native Helpline at 1-844-762-8483. In an emergency situation, please call 911.

The MMIWG2 Database logs cases of missing and murdered indigenous women, girls, and two spirit people, from 1900 to the present. The Database maintains a comprehensive resource to support community members, advocates, activists, and researchers in their work towards justice for MMIW. https://www.sovereign-bodies.org