By the Lower Phalen Creek Project

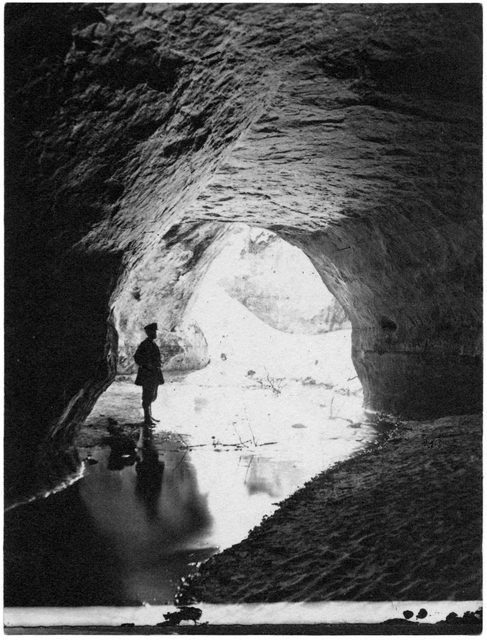

The first European known to have visited the area known to the Dakota as Imnižaska, or Saint Paul, was Jonathan Carver. In his journals from 1766-1767, Carver details encountering the place we know as Wakan Tipi when he writes about a “great stone cave called Waukon Teebee” by the local Dakota people. He describes the cave in great detail, including the abundance of rock art inside the cave’s entrance. He also mentions that “appearances of lights shining at a distance and strange sounds” coming from inside the cave were, at least in part, why the Dakota deemed this place both mysterious and sacred. After staying with the Dakota throughout the winter, Carver described his participation in the annual council meeting of eight bands of the Dakota on May 1st, 1767, inside that very cave.

It is nearly two hundred years later when Paul Durand, a non-Native man from Minneapolis, who, drawing largely from field notes and maps produced by Joseph N. Nicollet in 1838, and with assistance from Dakota elders and knowledge keepers – writes his book, “Where the Waters Gather and the Rivers Meet: An Atlas of the Eastern Sioux.” In this book and related map, Durand also describes this sacred site:

“Wakan Tipi (1) sacred (2) habitation. Carver’s Cave below Dayton’s Bluff, St. Paul. The common intersection of the roads of communication between the three original villages was precisely at this place. It was here the dead were brought, placing them on scaffolds then later burying them in the adjacent mounds – Jos. N. Nicollet.”

We again encounter this site in “Mni Sota Makoce,” in which Gwen Westerman (Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate) and Bruce White write, “despite extensive travels, [the Dakota] always brought the bones of their dead to this location,” signifying that this was a burying place for the Bdewakaŋtuŋwaŋ Dakota.

From these written records we find multiple authors referring to this cave site, and we find records of the site’s significance to the people – as a place for ceremony, annual councils, and as a final resting place at the mounds above the cave, in what is now Indian Mounds Regional Park. We also see multiple accounts tying the site to broader Dakota culture, describing an “intersection point,” or hub of social and religious activity for the Dakota bands of Mni Sota.

However, even with these written records, so much more about this site remains unwritten. Dakota life – the culture, the language, the geography, and the people – could never be quantified and cataloged in academic records alone. Dakota life and culture is a circle; we can’t fit it into the box Western culture has imposed on us. The name we use for this site reflects these complexities. As Carolynn Schommer writes in the introduction to the Riggs Dakota Dictionary, “Dakota language structure is much different from the English, and no literal translation can be made from either language into the other.” There also exists the fact that names for sites and “things” vary from community to community. Take the examples of Pejuta Sapa vs. Mnikata, as two ways to say coffee in the eastern Santee dialect – both are correct. The same holds true for this sacred site. Some Dakota speakers refer to the site as Tipi Wakáŋ, while others refer to the site as Wakáŋ Tipi. It is our stance, as the writers of this commentary, that both are correct.

Interestingly, both versions appear in Durand’s “Atlas of the Eastern Sioux.” In this book, though, where Tipi Wakáŋ is listed in the atlas of place names, it is not described as a traditional place name. Tipi Wakáŋ, according to Durand, describes a “sacred house, a church.”

Durand’s notes signify a distinction, linguistically and culturally, between the identification of a sacred structure or building, and the description of a specific place where sacredness dwells. Durand also lists Taku Wakáŋ Tipi, which could be translated as “Dwelling Place of Something Sacred” (Taku = Something). This site, according to Durand, is “a small hill, overlooking the Fort Snelling prairie located between the VA Hospital and the Naval Air Station. It was called Morgan’s Hill in pioneer times.”

Our exploration of these site names continues, and for the second part of this series, we will share the stories that are appropriate to be told in this format, from Dakota elders and knowledge keepers, about this place. And we know that in the Dakota community, there are multiple perspectives and relationships to place, even multiple ways in which Dakota people refer to this site. We honor all of those relationships and histories, even when they may conflict. We honor that different communities, and even different families within the same community, may have different stories about one place. And they are all correct.

To share oral history relating to this site, please contact Wakan Tipi Center director, Maggie Lorenz at: mlorenz@lowerphalencreek.org

or Mishaila Bowman at: mbowman@lowerphalencreek.org