By Deborah Locke

Sherman Alexie’s latest book is a memoir about his mother Lillian and a whole lot more. It’s a book that sits inside your head after you finish it, forcing you to feel what you’d rather not feel, and above all else, ensuring that you will never ever forget Lillian Alexie. Or her son, Sherman.

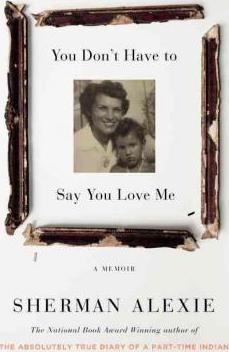

“You Don’t Have To Say You Love Me” is the story of a family from the Spokane Indian Reservation near Wellpinit, Wash. The book centers on Alexie’s relationship with his complex, blunt mother who often comes off as the least maternal mother imaginable. According to her son, Lillian was cruel and unpredictable, oppressive, intelligent and arrogant.

In 2015, Lillian died from cancer at age 78 at the family HUD-built home. Alexie’s grief and loss permeate the book about reservation life and death even as he introduces people you wished you had known while they were alive.

If the above sounds like a contradiction – and a downer – know also that this is a story of survival, of reservation humor and irony, and of insight and wisdom. The lives unfold in word bits through a swirling narrative of prose and poetry, with facts scattered the way patches seem to be scattered on a quilt.

Yet there’s a cohesive structure to the book, the way there’s a cohesive structure to a quilt. Sherman’s mother was an expert quilter, and the income generated from the quilts she sold paid for food and other necessities. Her son Sherman showed an early affinity for written words; with time, he became famous and a best-selling author. This book stitches the mother/son relationship together with many other pieces – Spokane tribal history, Sherman’s brain surgery and recovery, grade school bullying, criticism of Donald Trump supporters, genocide, fame, family secrets, reservation abandonment, first kisses and way more.

But it’s that mother/son dynamic that keeps returning to center stage. At his mother’s funeral, Sherman looked around at the mourners and realized how he had always wanted to be beloved by them, yet he had left the reservation to attend a high school 22 miles away and never returned.

“Between me and my tribe, I didn’t belong because maybe I never wanted to belong. When everybody else danced and sang, I silently sat in my room with books…I used books for self-defense.”

Permitting her son to leave home in 1979 and receive an education in a white community was one way Lillian saved Sherman’s life, he wrote. He grew in confidence at the high school and became a class standout both academically and athletically.

Lillian also saved his life, and that of his siblings, when she quit drinking alcohol in 1973 and focused on her children’s safety. She remained a dry drunk for the rest of her life, flying into and out of rages and taking her anger out on whoever was closest to her at the time. Often that was Sherman, her “most regular opponent. I remember only a little bit of my mother’s kindness and almost everything about her coldness.”

Yet in a poem about quilting, he wrote how he missed his mother, the rebellious trickster with her inconsistent mothering. “She taught us survival with needle, thread and thimble all stained with her blood,” he wrote.

He also wrote of other important women in his life. Sherman’s wife Diane is his bedrock and by the end of the book, you wish Diane would write her own memoir. His twin sisters pop up here and there, providing comic relief and perspective for their brother. And there are small vignettes of everyday life, like doing laundry at home with Diane, where Sherman perversely refused to fold clean clothes, but happily ironed them to perfection.

It’s those little excerpts that bring humanity and lightness to the story, like the wonderful description of Lillian frying baloney that curled at the edges and rose, whose sizzle was one of Lillian’s love songs. Like the story of a kind, competent nurse who cared for Sherman after his brain surgery. Like the “Edith Whartonian social rules of the reservation” which will be immediately recognized by those familiar with reservations.

This is a book with staying power, a book that won’t leave your head soon.

Sherman Alexie, Jr. is a Spokane-Coeur d’Alene-American novelist, short story writer, poet, and filmmaker best known for the movie “Smoke Signals.” He has won the Pen/Faulkner Award, the National Book Award, and the Sundance Film Festival Audience Award. Alexie lives in Seattle with his wife, Diane. They have two sons. He will participate in the Season Opener of the Talking Volumes Series on Sept. 14, 2017 at the Fitzgerald Theater in St. Paul.