Hundreds of

Hundreds of

protesters gathered outside the Hubert H. Humphrey Metrodome in

downtown Minneapolis on Nov. 7 to speak out against the Washington

mascot. According to Little Earth Education Director Sasha Houston

Brown, the rally was the site of some clashes between football fans

and Indigenous protesters.

“There were

some very intoxicated white football fans getting in people’s faces,

mocking the drums, making fake war whoops, doing fake dances,” she

said. “We can’t say there’s not an issue when that’s going on.”

There are

strong feelings on both sides of this debate. In social media posts

that argue to keep the mascot, a common theme admonishes protesters

to “get over it.” In Google + user Ron Brown’s words, “this PC

group of rejects have almost destroyed our society."

Another common

argument in favor of the mascot is that it is an honorific. To this

end, Washington team manager Dan Snyder invited Navajo Code Talkers

to the team’s game on Nov, 25. “The

#Redskins

celebrate &

honor members of the Navajo Code Talkers,” read the team’s official

Twitter posts about the event.

Is this a

superficial issue of offense, over sensitivity, or political

correctness? If not, why do mascots and the popular depiction of

Native Americans matter, not just to Native communities, but to

American society as a whole?

“Their

ignorance isn’t just out of nowhere, it’s reflective of the

collective American ignorance,” said Brown of mascot supporters.

“It just speaks to the more complex notion of the history of

America and the history of First Nations and Indigenous people and

the fact that America is still not ready as a society to take a hard

look into our past and openly talk about what happened.”

Taking a hard

look at history and future movements for social justice within both

our education systems and society at large is at the core of the

mascot debate.

“It’s not

about blame, it’s not about shaming people, and it’s not about white

guilt, but it’s about doing justice and speaking the truth about

things,” Brown said. “We can’t really have conversations about

race and identity and cultural appropriation and mascots and imagery

without looking at these core issues that are really central to the

debate.”

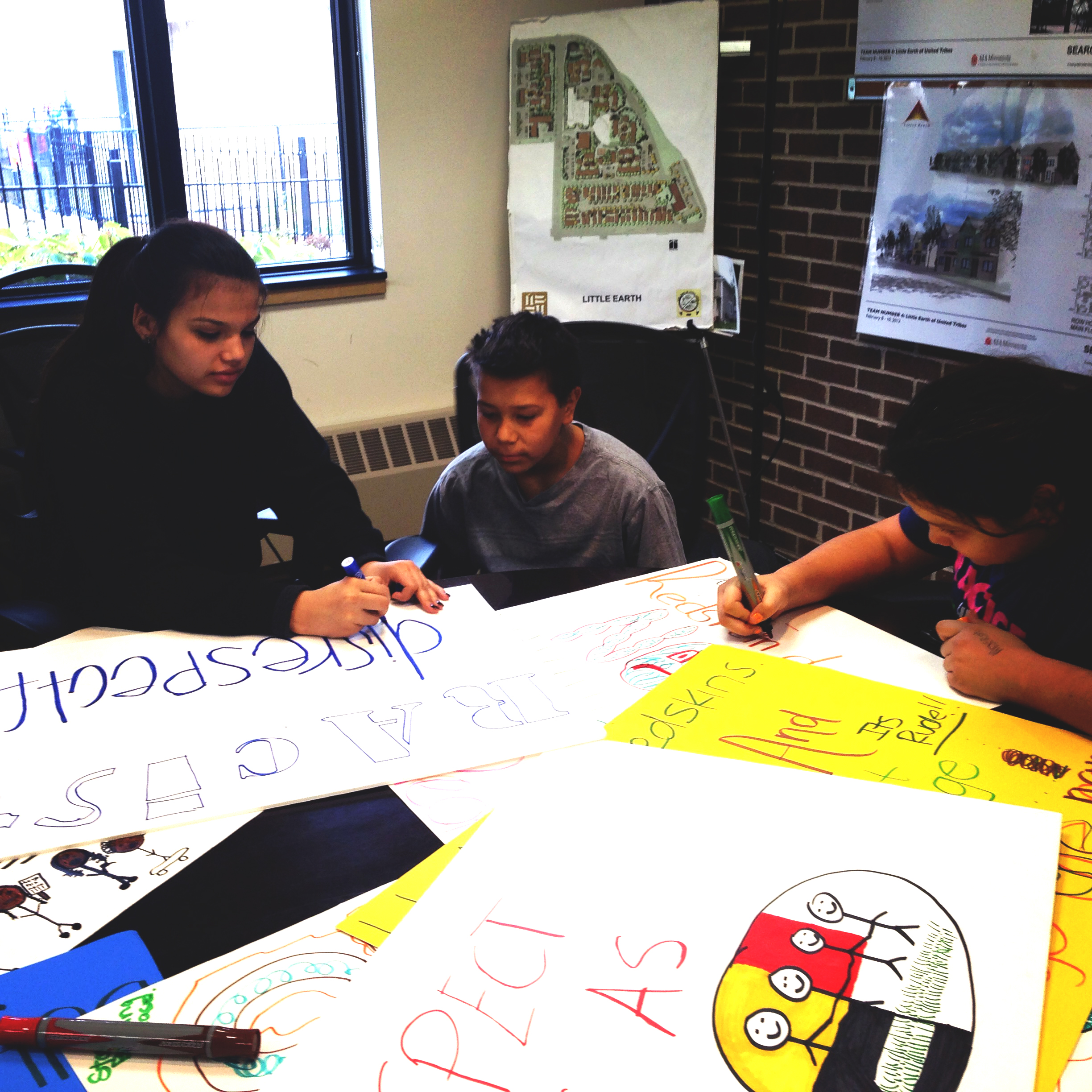

Brown, a

member of the Santee Sioux Nation, helped organize a Native youth

march shortly before the larger protest.

“On the one

hand, I thought maybe I shouldn’t even get involved in this issue

because there is so much going on in my community and I don’t want to

get pegged as someone who just talks about cultural appropriation or

stereotypes,” she said. “But it was really when I thought about

our young people and the ways that this does impact them and the ways

it impacts us all [that I got involved].”

In 2004,

several researchers conducted a psychological study on the impact of

mascot imagery on Native American youth entitled “Of Warrior Chiefs

and Indian Princesses: The Psychological Consequences of American

Indian Mascots.” This four-part study involving youth from

different reservations found that “exposure to American Indian

mascot images has a negative impact on American Indian high school

and college students’ feelings of personal and community worth, and

achievement-related possible selves.”

Brown feels

that these are some of the most compelling reasons to advocate for

mascot changes.

“You think

about being a Native child and the only time that you see yourself in

media is as a sports mascot or a costume or you see the rare very

depressing news story,” she said. “It’s all negative and they

don’t see themselves portrayed as they are and as they should be.”

This imbalance

in the portrayal of Native people in the media takes its toll on

Native youth across the country.

“Native

youth have the highest rates of suicide among any ethnic population

in the United States – the statistics are staggering,” Brown said.

“I’m not saying sports mascots are directly causing suicide, but we

have to look at the the messages [Native youth] are receiving,

explicit or implicit, from dominant society around who they are and

their own value.”

Brown says

that one of the factors that contributes to these dominant

stereotypes is a denial of the present lived experiences of Native

people.

“When we

talk about Natives, whether it’s in a political climate or a social

climate, it’s from this past, romanticized Indian experience,”

Brown said. “We don’t talk about contemporaneity for Indigenous

people and that invisibility contributes to things like having the

Redskins be acceptable … When you have a derogatory racial

caricature and name like the Redskins, it’s somehow OK because

[people] can’t place it with a friend, a family member, a child that

they work with on a daily basis. They can’t place it within a

relevant personal context, and so in a lot of ways that human element

is completely void in the debate.”

The

dehumanization of Indigenous people and communities has far-reaching

consequences.

“When we

look at some of the acts that are happening to tribal people on

tribal lands, those can only take place as long as our cultures and

people are seen as dehumanized and other,” said Brown. “In no

other circumstances would you be contaminating the water, putting

pipelines through, passing legislation where these communities can’t

even prosecute crimes that happen on their own lands.”

Brown says

that as long as Native people are viewed as caricatured mascots, many

of the more tangible issues and injustices Indigenous communities

face will continue.

“When you

have your nation’s capitol’s team named the Washington Redskins, that

epitomizes the way that Native people are looked at and depicted in

our nation and society,” said Brown. “As long as we continue to

be viewed as a mascot, all of these issues will continue to persist.”