By Eddie Chuculate

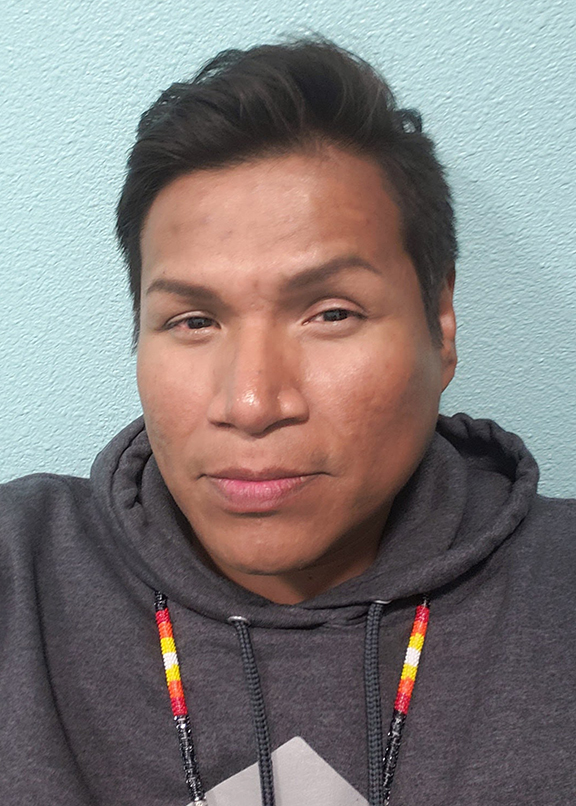

Outreach worker Jase Roe is determined to prevent a Native American homeless camp from exploding into one similar to 2018 that grew to over 300 people, garnered national attention and was dubbed “The Wall of Forgotten Natives.”

Although located on the same state-owned property, this fall’s “Wall” is strictly about getting Natives housed with winter encroaching, and with long-term goals of something permanent.

“We came here a few weeks ago to draw attention,” said Roe, 44, a Northern Cheyenne from Lame Deer, Montana., who was adopted and grew up in the Twin Cities suburb of Eagan. “Now that that’s done, we’re working on real resources and a permanent solution.”

Rioting in late May after the death of George Floyd at the hands of Minnesota police left even more people homeless in a city already struggling with a shortage of affordable housing and beds for the indigent.

A Christmas Day fire that destroyed a downtown hotel that had been converted to transitional housing, leaving 250 homeless, didn’t help. Tent cities sprang up this summer in numerous public parks in a city ranked No. 1 in the US in 2020 for its parks system by the Trust for Public Land.

A number of those camps reportedly became problematic with sexual assaults, fighting, littering, rampant drug and alcohol use and burglaries and vandalism in neighborhoods adjacent to the parks. Camping in public parks in Minneapolis is illegal. But due to the pandemic and extraordinary circumstances, the city allowed it this summer.

Some residents in the parks’ nearby neighborhoods welcomed it, even campaigned for it, carrying signs and petitioning Mayor Jacob Frey and the city’s Parks Department.

But some were against it from the start, and when police were called twice on alleged sexual assaults involving minors to the largest encampment at Powderhorn Park in the city’s South Side next to a school zone, officials pulled the plug.

A two-week notice was issued before park police dismantled lodgings that were left behind, bulldozing tents and abandoned property into piles. The Powderhorn Park encampment had grown to 560 tents by July 9.

One of those ordered to disband was a camp for mainly Native Americans surrounding the Franklin Avenue Corridor where many Native-administered organizations, housing, businesses and other services such as medical clinics and social agencies like the Minnesota Indian Women’s Resource Center (MIWRC) are located. It was deemed uninhabitable.

“There was a lot of (sex) trafficking issues with our women going on, gunfire and other violence,” said Roe, who works for the MIWRC. “Me and (co-worker) Jenny Bjorgo (43, Ojibwe/Wind River) decided to help the campers find a new place to stay.

“I can’t really say how it happened, but we ended up at the Wall.”

The MIWRC is a Minneapolis nonprofit that provides a range of housing, drug treatment and mental health programs for Indian women and their families.

“As a small nonprofit organization, we have expended resources and countless volunteer hours to provide protection and services to our clients and Relatives at the Wall,” said MIWRC President and CEO Marisa Miakonda Cummings (Umonhon/Omaha) in a statement.

“We call upon the city, county and state to find immediate solutions to homelessness and to expend resources to fully realize these solutions.

“It is not the responsibility of the private sector or small nonprofits to do the work and expend resources to fix a systemic problem caused by U.S. policy,” said Miakonda Cummings.

In a news release, Minneapolis city officials said they cleared the previous encampment because of health and safety concerns and with help of nonprofit organizations. They were expected to meet with the state and county to talk about how to assist campers who moved back in.

Native leaders, including Clyde Bellecourt, a founder of the American Indian Movement, held a news conference at the beginning of September urging the city, Hennepin County and the state to find suitable, long-term housing for the homeless.

“I feel sorry for them. It’s pitiful what we have to do and the effect it has on our community,” said Bellecourt. “We can’t just sit around and think about where we’re going to put up a camp next.”

The Wall, on property owned by the Minnesota Department of Transportation, is just a narrow strip of land along a highway sound barrier near Hiawatha and Franklin avenues in south Minneapolis not far from the Little Earth housing project, which is considered the nation’s only urban housing development dedicated to Indians.

The Wall property had been padlocked for nearly two years by the state after the original encampment disbanded in late 2018.

“I won’t say how they (gates) were opened, let’s just say they were taken down,” said Roe. “We instructed campers to immediately start setting up tents because when you have 10 set up that’s considered an encampment, and by the governor’s (Democratic Gov. Tim Walz) orders you can’t do a sweep and take down an encampment right now due to COVID.”

State troopers were soon called to the site and a standoff occurred, spearheaded by Roe.

“Me and Jenny have contacts, connections in the community,” Roe said. “I have Jacob’s (Minneapolis Mayor Frey) number in my phone and people right under the governor.

“We made some calls and were told to hold our ground. As soon as our relatives were unpacking (from the old encampment) troopers went around telling them to pack back up.

“I told them (troopers) they couldn’t do that. We stood our ground. At that point my blood was boiling, we were in it. Who are you, kicking Natives off Native land, I told them. Where are our people supposed to go? I told them you are about to get a call telling you to leave.”

“We stood our ground for a good three hours, and eventually they all left,” Roe said.

In a stunning reversal in mid-September, state troopers and Hennepin County sheriff’s deputies were patrolling the encampment, keeping out an undesirable element of drug use and sales and sex-trafficking attempts, Roe said.

Roe said Bjorgo has a roster of people from the original encampment near MIWRC who belong at the Wall. Others are discouraged from coming, Roe said.

“Once we got started and got services coming in, medical and people with housing and other advocates, and regular meals, security, we started getting calls from other agencies asking if we had more space.

“I was like, you have GOT to be kidding me.”

The current Wall contained around 125 people at its maximum population, Roe said. It’s down to around 30-40 clients, now, he said.

He’s determined to keep it from becoming a media sideshow and the homeless hot spot it became in 2018, where at least two people died, several cases of the staph infection MRSA were recorded due to the cramped side-by-side conditions of over 300 people, and rampant, open heroin and opioid use was common, along with fights and other disruption including disputes over who was in charge.

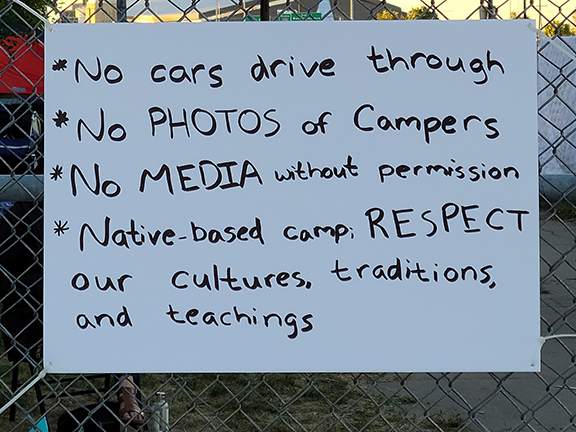

At that camp, social services advocates weren’t welcome, and even threatened, Roe said. At this one, they are more than welcome, and encouraged. Signs are up prohibiting pictures of the campers and media swarms.

Even the tipi that became the symbol of the 2018 camp and which was erected at this encampment, too, is no longer welcome, Roe said.

“People were in there shooting up. We told the people who put it up it was OK if they stayed with it and guarded it, but, no, they left. We told them we want it taken down.”

Roe became emotional when describing the current situation.

“These campers, these are people from the neighborhood with families. Grandmothers who are mothers of mothers with babies. Whole families,” he said.

Roe said he’s grateful to people like American Indian Movement activist Mike Forcia (Bad River Ojibwe), and Michael Goze (Ho-Chunk) director of the American Indian Housing Development Corporation in Minneapolis, and their crews, for providing security and safety at this encampment.

Through a partnership with the Red Lake Ojibwe Nation and social services agency Avivo, 63 people have been moved to a hotel in Coon Rapids, Minnesota, a suburb 20 miles north for a three-month stay.

“We go by with our master list every time more beds become available and ask if they’re ready to go,” Roe said. “Our goal is to get them out of here, and not let it get out of hand like in 2018. It’s not ideal, I don’t like taking our people out of the city, out of their home, to the outskirts like that, where if you don’t have transportation, which most people don’t, you’re stuck. But it beats this.”

Roe wishes more Natives would become involved with helping the Native homeless population.

“To the doctors, lawyers and other successful business people, people like that who have made it to the other side, get involved with the community. We’ve got to take care of ourselves.”

Roe was touched by the contributions of a Somali woman who has been donating 100 home-cooked meals daily.

“She doesn’t want any recognition. She comes from a community herself that has been down and profiled, getting the short end of the stick, a lot of stigma. For a community member to do that is really touching. We had a guy come and drop off a whole cord of wood.

“This is hard work coming out here every day,” said Roe, who quarantined at home a few days before testing negative for the coronavirus. “This runs totally on volunteers. Most of us have regular 9-5 Monday through Friday jobs and come out here when we can. Some of our women and other vulnerable relatives can still come under attack at night. That’s when we need people.”

And unlike 2018, when the Wall and its problems only multiplied over months, the aim now is the opposite.

“Our ultimate goal is to close this camp. I’d like to see it gone within two weeks,” Roe said.