By Lee Egerstrom

Medical researchers and officials in Duluth insist the opening of a Johns Hopkins University research hub with existing staff from University of Minnesota Medical School should be viewed as an expansion, not a substitution, for ongoing research on American Indian health.

Johns Hopkins’ Center for American Indian Health is opening a Great Lakes Hub research program in October to work with 11 Ojibwe tribes in Minnesota (5), Wisconsin (2) and Ontario (4). It follows a move across town for Dr. Melissa Walls, a social science researcher, and a staff of 12 that has been doing similar work at the University of Minnesota Medical School campus in Duluth.

Dr. Mary Owen, director of the Medical School’s Center of American Indian and Minority Health (CAIMH), said Minnesota educators and researchers intend to work closely with the Johns Hopkins team going forward. Walls said that is her team’s goal as well. She will also retain an adjunct professor’s role with the Medical School at the UMD campus.

The staff’s shift to the Great Lakes Hub, as Johns Hopkins calls it, is greater that the number of people employed in Duluth. Walls said she has a network of 107 people at reservations, clinics, schools and the general population in the western Great Lakes’ border region.

As is always the case with public institutions, the Minnesota Medical School depends on public support through the University’s Board of Regents and state appropriations. That, ultimately, will determine how University medical school programs and research are supported on Native health issues.

Johns Hopkins said Walls will serve as director and also hold a position as associate professor of International Health at its Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore.

For Johns Hopkins, opening operations in Duluth represents a major expansion of its long-established Native American health initiatives that have mostly been centered in the American Southwest. It has operations at Gallup, Tuba City, Shiprock, Fort Defiance and Chinle, in the Navajo Nation; and at Fort Apache and Whiteriver, among the White Mountain Apache.

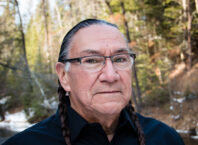

Walls, a member of the Bois Forte and Couchiching First Nation bands, is originally from International Falls. Over the past 12 years with the medical schools, she has led or participated in research on the causes or origins (etiology) of diseases, consequences, and preventive interventions for diabetes, substance use, mental disorders and physical health issues among Native people.

She will work with tribal partners to expand Johns Hopkins’ Together on Diabetes program from the Apache and Navajo hubs. With it, the Great Lakes staff will reach out to adults with diabetes and their adolescent children on three Minnesota and two Wisconsin reservation to help manage and prevent diabetes, she said.

“It’s often hard to change the behavior of individuals. You can have a bigger impact if you get family norms to change,” Walls said in a statement for Johns Hopkins.

Walls told The Circle that she and her team are excited about joining Johns Hopkins because of its “massive reach, advocacy power and strong relations with the National Indian Health Service.” What made the move possible, she added, is that the research team can remain in Duluth and near the reservations and people with whom they’ve been working.

Dr. Owen and University of Minnesota Medical School leaders said the university must continue training researchers and medical professionals, as it always has.

“There is no questions that we (American medicine) are short of talented researchers for our Native populations,” Owen said.

The University’s Medical School plays an important role in reaching Native Americans, for both health care and for medical education.

The Duluth campus held a White Coat Ceremony on Aug. 16 welcoming 65 incoming medical students for the class of 2023. Of them, 12 were Native Americans.

The Association of American Medical Colleges ranks Minnesota as second to the University of Oklahoma in producing Native American physicians. The University counts 177 American Indian and Alaskan Native physicians among its graduates.

Owen, a Tlingit from Alaska, is one of them. She graduated in 2000, returned to her home area around Juneau as a physician, and then came back to the University in 2014 for an endowed position in American Indian Health and as director of the Center of American Indian and Minority Health.

CAIMH and the Minnesota Medical School has a long history in serving the Indian communities and that isn’t changing, Owen said. The center was authorized by the Minnesota Legislature in 1987 and strives to build interest among Native and minority people to become physicians, pharmacists and other health professionals.

Some of these efforts and affiliated programs merit a closer look in future editions of The Circle. Here are a few ongoing programs directly tied to Minnesota’s Native communities:

The American Indian Learning Resource Center works to help the cultural, academic, supportive and social environment for Native students at the UMD campus.

Innovators of the Future is a community based science program in which biomedical science educators at Duluth work with the Bois Forte Band and Grand Portage Band communities to design curriculum for science education in elementary schools.

Memory Keepers Medical Discovery Team, or Memory Keepers MDT, is research by University of Minnesota medical professionals on the relationship between vascular dementia and diabetes in tribal communities. It seeks to reduce health disparities for people living in remote communities far from medical services found in urban areas.

In addition, Dr. Anna Wirta Kosobuski, an assistant professor of biomedical sciences, leads several efforts connecting STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) and STEAM (also arts) curriculum for different grade levels and for summer programs at reservations and the Duluth campus.

In other medical news, ongoing controversy within the Minnesota Department of Human Services expanded in August with the revelation that DHS had apparently overpaid the White Earth Nation and Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe by $25.3 million for substance abuse treatments under the federal Medicaid program. While the tribes showed correspondence they were following advice from DHS, state officials said they are obligated to try to recover the over-payments from the tribes. How this plays out had not been determined.