By The Circle

Fears of immigration sweeps have intensified across Minneapolis and St. Paul as reports continue to surface of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officers, some allegedly wearing masks, detaining individuals based on skin color. City leaders are urging residents to remain vigilant and to immediately report suspicious enforcement activity, particularly when officers refuse to identify themselves.

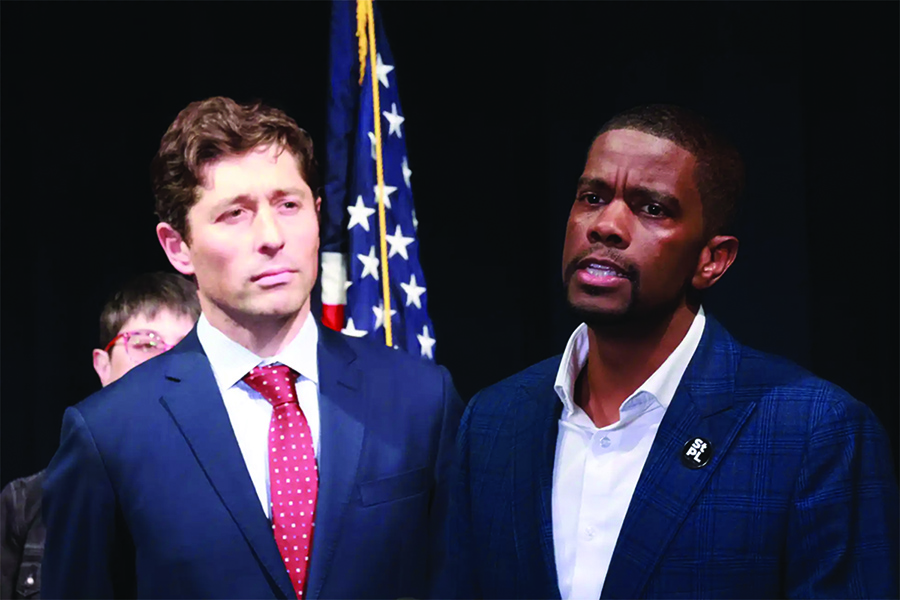

Concerns have been growing in the Twin Cities Somali community following news from The Associated Press and The New York Times that the Trump administration plans to deploy up to 100 additional ICE agents to Minnesota to seek individuals with final deportation orders. Minneapolis Mayor Jacob Frey said the reports are credible. “Obviously, this is a frightening moment for our Somali community,” Frey said, describing the expected ICE surge as “terrorizing.” He added, “That’s not American. That’s not what we are about,” according to the article from MPR News.com.

Frey said he is worried that federal agents searching for undocumented individuals will mistakenly detain lawful residents and U.S. citizens. “They’re gonna get the wrong people,” he said. “They’re gonna screw it up so badly,” he added, noting that Minneapolis has more than 80,000 Somali American residents, the overwhelming majority of whom are legal residents or citizens.

Minneapolis Police Chief Brian O’Hara emphasized that the Minneapolis Police Department does not assist ICE with immigration enforcement. He told residents to call 911 if they encounter individuals claiming to be law enforcement who refuse to identify themselves. “That’s something you should report, and we will immediately respond to and document,” he said, urging peaceful protest if enforcement actions escalate.

The warnings come as Indigenous residents nationwide raise alarms that Native Americans are being detained by ICE despite being U.S. citizens and citizens of sovereign tribal nations. In Washington state, well-known Native American actor Elaine Miles, best known for her role in “Northern Exposure,” reported being stopped by four masked men identifying as federal agents while she walked to a bus stop in Redmond. Miles told The Guardian that she showed the men her tribal identification from the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation in Oregon, but one officer told her “anyone can make that.”

The ICE agents refused to verify the card by calling the tribe. Miles called the number herself, and when one officer tried to take her phone from her, she resisted. The men ultimately released her and drove away without explanation.

Miles said this was not an isolated experience. She told the Lakota People’s Law Project that similar things have happened to her son and uncle. “Tribal IDs—the government issued those damn cards to us like a pedigree dog! It’s not fake!” she said.

Indigenous rights attorney Gabriel Galanda told The Seattle Times that these incidents reflect racial profiling. “People are getting pulled over or detained on the street because of the dark color of their skin,” he said. He added that the refusal to recognize tribal identification shows “a fair amount of ignorance about tribal citizenship generally in society and in government,” and said it is “deeply troubling that in 2025, the first people of this country have to essentially look over their shoulders.”

A similar case occurred in Des Moines, Iowa. An article in Native News Online reported that 24-year-old Leticia Jacobo, a member of the Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indian Community in Arizona, was nearly transferred into ICE custody after being booked for a suspended license. Jacobo, who was born in Phoenix, had been held at the Polk County Jail and was scheduled for release Nov. 11, but jail staff told her mother that she would instead be handed over to immigration agents.

The article described how Jacobo’s family rushed to the jail with her birth certificate and her tribal identification, but staff insisted she would still be deported. Her aunt, Maria Nunez said, “They’re going to go ahead and deport her to wherever they’re going to take her, but we have no information on that.” Jacobo was released only after her family kept watch outside the jail overnight to ensure ICE did not remove her.

“It’s racial profiling,” Nunez said. “She’s been there before, they have a rap sheet on her — why would they make a mistake with someone that’s constantly coming in?” Polk County officials later called it a “clerical mix-up,” but the ICE field office declined to explain how it verifies detainers or prevents Native citizens from being detained. Nunez said she fears others may not be as fortunate. “Not everyone has a family as involved in their welfare as Jacobo does,” she said.

These events have heightened fears across Native communities in the Twin Cities, especially among those who regularly carry tribal identification rather than state-issued IDs. Minneapolis Indigenous advocates say masked agents are a particular concern. When individuals wearing tactical gear refuse to show badges, residents feel they are being confronted by unknown actors with police-like authority.

The atmosphere of fear has also intensified for Somali Americans. Gov. Tim Walz said he expects “an increased presence of immigration folks in our city,” following Trump’s disparaging remarks about Somali immigrants. Trump has claimed that Somali Americans are too reliant on welfare programs and add little to the United States. “I don’t want them in our country,” Trump said during a Cabinet meeting, according to the MPR News report. Trump also referred to Somalia as “barely a country” and said Somali people “just run around killing each other.”

Walz criticized the remarks as a political strategy targeting immigrants. “This is a president in spiral doing nothing to make life cheaper for Minnesotans or Americans,” Walz said. “We understand who he’s targeting.”

Indigenous advocates say both Native and Somali Americans are facing a common threat: enforcement actions that appear to rely on assumptions about who belongs in this country based on skin color rather than legal status. “Whether you come from Somalia or were born here as Native, we are facing the same fear from the same people,” one Minneapolis Native community organizer said.

Tribal nations and community groups are working to prepare. Leaders are creating rapid-response communications networks and providing training on what to do if confronted by law enforcement officers who refuse to identify themselves.

Residents are being encouraged to keep proof of citizenship accessible, remain aware of their surroundings, and notify authorities if they feel unsafe. The message from Minneapolis officials is consistent: if someone claiming authority refuses to identify themselves, residents should question the interaction and call 911.

Frey insisted that the city will stand firm with immigrant and Indigenous residents. “The rights and dignity of immigrants — and all Americans — must be upheld,” he said. Many community members fear that as winter sets in, the threat of masked agents detaining people without clear cause adds a chilling new layer of danger to neighborhoods already struggling with ice, cold and mobility challenges.

Federal officials have not commented publicly on the reports of increased ICE enforcement in Minnesota, nor have they responded to concerns about Native Americans being detained. Advocates worry that without strong oversight, masked arrests and identity challenges could escalate. An elder living near the Little Earth community in Minneapolis expressed frustration and disbelief that such precautions are necessary. “We are the first people of this land,” she said. “Now we’re treated like strangers in our own homelands.”

Frey warned that any enforcement operation involving masked officers or unverified authority figures “can’t go wrong.” His concern remains that “people’s lives and rights are at stake.” Indigenous and Somali residents continue to hope that heightened awareness and community vigilance will prevent wrongful detentions and protect the rights of all who call the Twin Cities home.