By The Circle

A surge of Native American authors helped reshape bookshelves in 2025, bringing new attention to Indigenous literature across the United States. As the calendar turns toward 2026, that momentum is expected to continue, with new releases in fiction, nonfiction, memoir, poetry and genre-blending works reaching wider audiences than ever before. Books from both emerging and established Indigenous writers are finding a place in major publishers’ catalogs, library collections and recommended reading lists.

Readers searching for authentic representation, cultural knowledge and compelling storytelling are discovering more choices from Native authors than in previous years. Librarians and Indigenous literary advocates say that while attention often peaks during Native American Heritage Month, the demand for Indigenous voices is becoming steady and year-round. Many new works explore identity, history, trauma, family, survival, language and relationships to land. Others experiment with futurism, horror, romance and coming-of-age narratives.

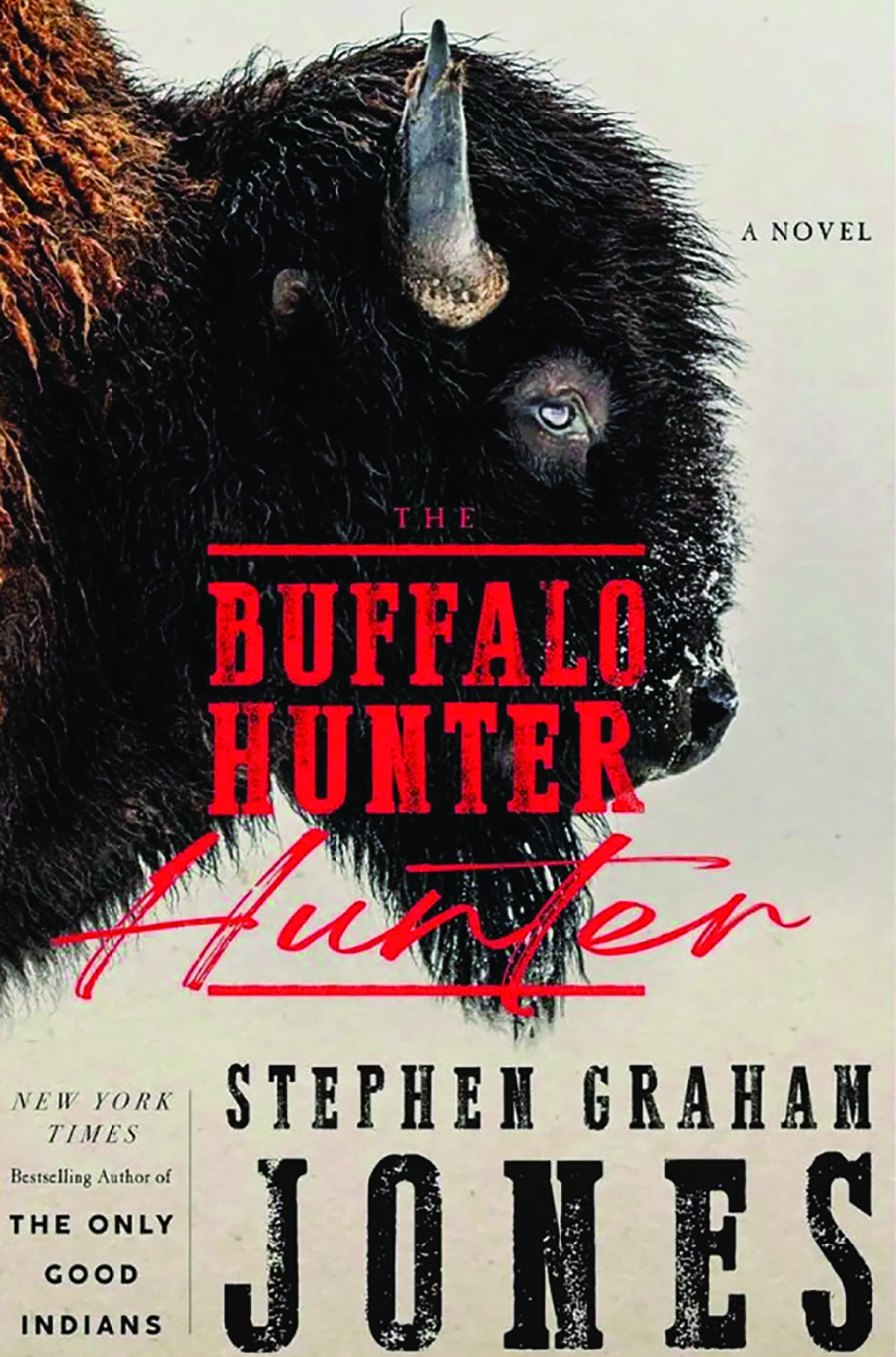

One headline release this year is “The Buffalo Hunter Hunter,” (No, that is not a typo) by Stephen Graham Jones, published in March by Simon & Schuster. Jones (Blackfeet Nation) has become one of the most recognized Indigenous voices in contemporary fiction. His work often merges elements of horror with lived history. The new novel takes readers into a fierce story of transformation and justice, told through a bold style that appeals to a wide range of readers. Booksellers report that Jones’ growing audience has brought new readers toward Indigenous literature as a whole, particularly those seeking darker themes with cultural depth.

Also widely discussed in 2025 is “Sisters in the Wind,” the latest young adult novel by Angeline Boulley, an enrolled member of the Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians. Boulley’s earlier bestseller introduced many readers to Indigenous voices through the lens of crime fiction. Her newest title continues her focus on Native youth, identity and determination. Young adult librarians say Boulley has been critical in expanding representation for Native teenagers in mainstream publishing.

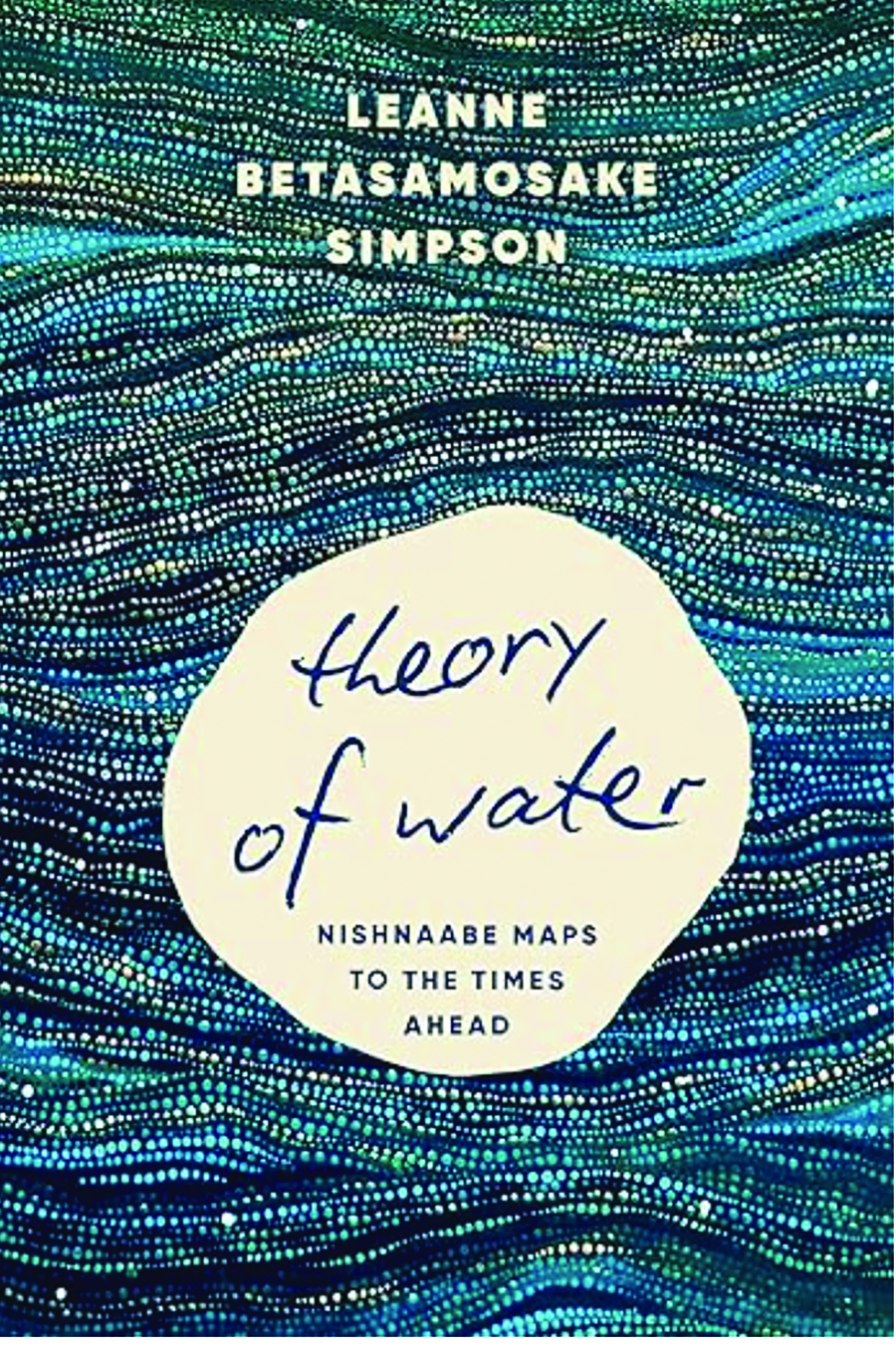

Indigenous nonfiction has also taken a more visible role in bookstores this year. One title already generating attention is “Theory of Water: Nishnaabe Maps to the Times Ahead,” by Leanne Simpson, released in April. Simpson is Michi Saagiig Nishnaabeg from Alderville First Nation in Canada. The author explores Indigenous relationships with land and water, weaving cultural knowledge with contemporary environmental reflection. Educators can use the book to fill the gaps in environmental literature by grounding ecological questions in community and memory rather than abstract theory.

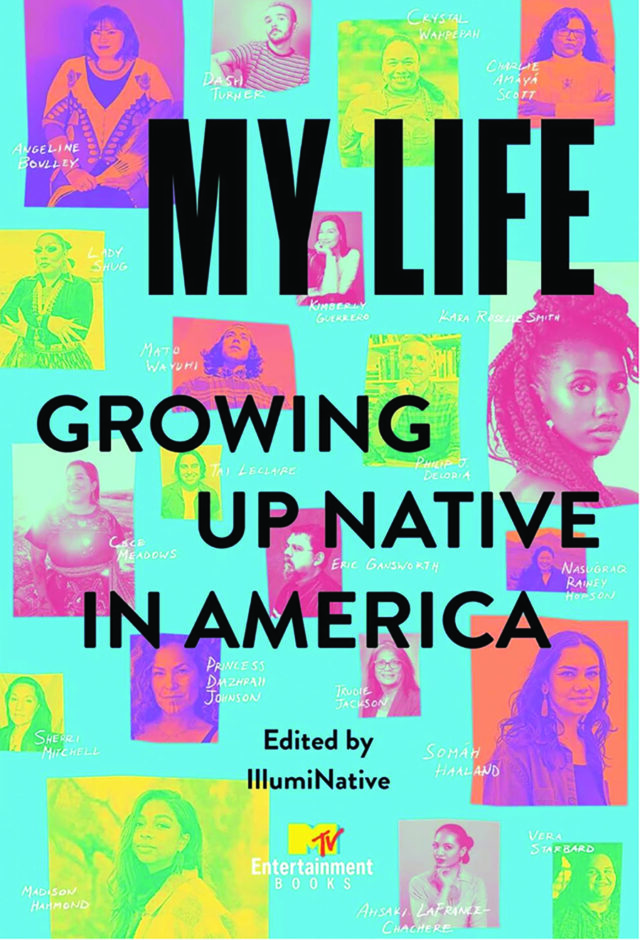

Anthologies remain central to Indigenous publishing efforts as well. “My Life: Growing Up Native in America,” edited by an Indigenous-led creative organization, offers essays, poetry and personal reflections from young Native writers. The collection examines what it means to navigate identity, belonging and future dreams while living within the United States. Teachers adopting the book in high school and college courses say that it is valuable for showing Native youth in their own voices rather than through an outside lens.

Another nonfiction title gaining attention is “The Indian Card: Who Gets to Be Native in America.” The book tackles questions that have long stirred debate: tribal enrollment, cultural identity, legal designations and the lived consequences of defining who is and is not Native. Scholars say the work arrives at a moment when many Native people continue to confront stereotypes and misunderstandings about heritage and sovereignty. The author examines the tension between legal definitions and personal identity, and the social impact of identity policing inside and outside Native communities.

Publishers and retailers say the interest in nonfiction and critical Indigenous voices indicates that readers are not just looking for stories but also for context, history and answers. Books that confront policies, boarding school trauma, land disputes and erasure are finding new urgency among Native and non-Native audiences alike.

Books in 2026

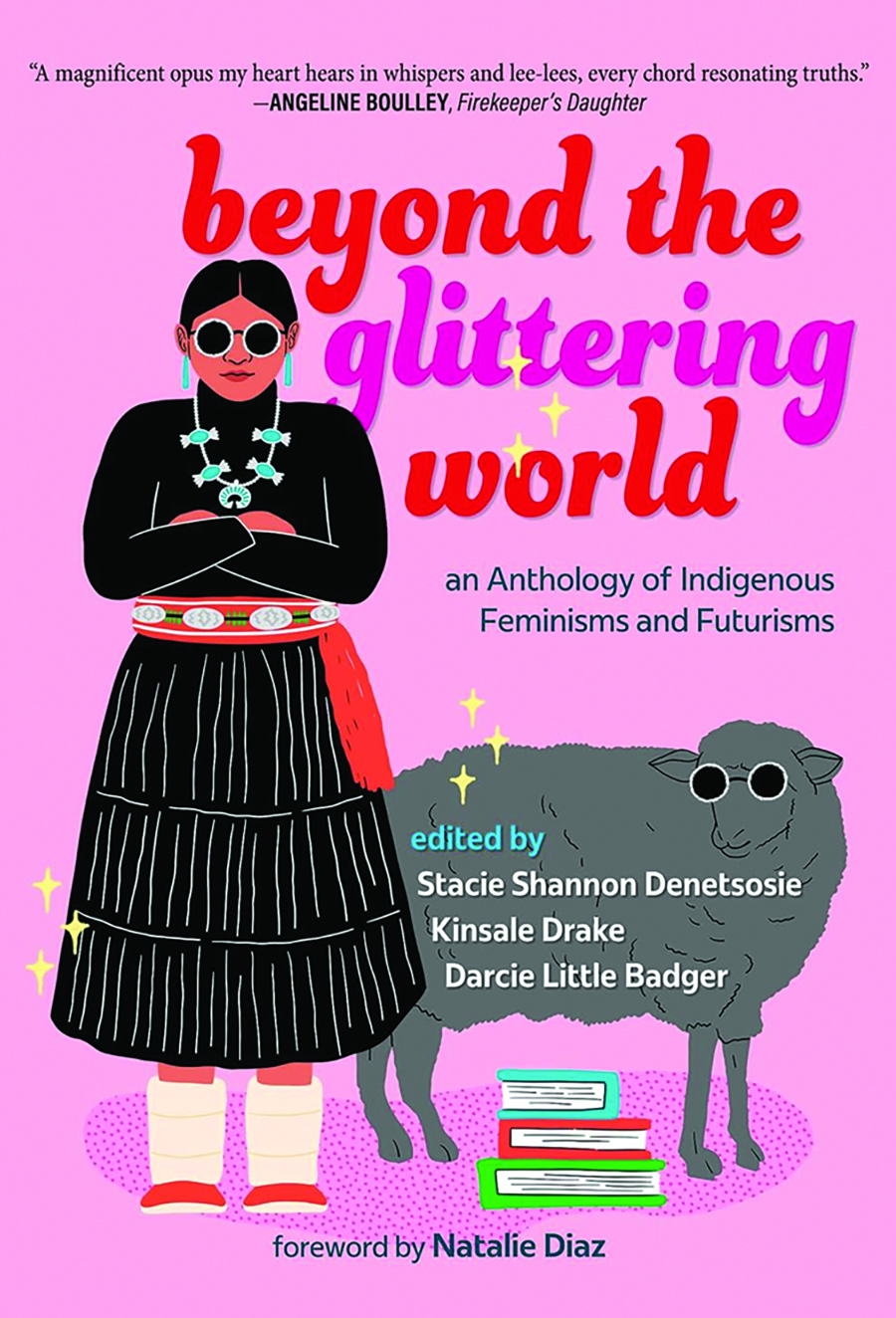

Looking ahead, several Indigenous-authored books are set to arrive in late 2025 and early 2026. One is “Beyond the Glittering World: An Anthology of Indigenous Feminisms and Futurisms,” published in late November. The anthology collects poetry, short stories and essays from Indigenous women and gender-diverse writers. Literary critics say it highlights voices leading conversations about gender, sovereignty and the future of Indigenous communities. The book has been promoted as a chance to see how Indigenous storytelling continues to evolve while maintaining deep connection to culture and history.

Another group of releases expected in early 2026 includes titles such as “Stronger Than,” scheduled for late January, and “We Can’t Wait to Hold You,” planned for February.

Book industry analysts point to several factors behind the rising interest in Native American books and literature. Library and school demand for inclusive literature has grown, and Indigenous authors are finding more opportunities with major publishers rather than relying solely on small presses. Additionally, social media communities built around Indigenous identity, book discussions and activism have helped readers discover Native writers more easily.

Native leaders in publishing also stress that the rise in Indigenous authors is not a sudden trend. Many point to decades of advocacy by Native writers, educators and cultural workers who pushed for space, recognition and the right to define their own narratives. Some of this year’s new writers credit tribal college programs, community literary circles, and Indigenous-centered mentorship efforts as foundational to their careers.

In addition to adult fiction and nonfiction, children’s and middle-grade literature are showing noticeable growth. Educators say younger readers are being introduced to Indigenous characters in ways that break from outdated storytelling stereotypes found in older books. New picture books feature Native children at the center of their own stories, participating in contemporary life while staying connected to cultural roots.

As book publishing gets easier and easier with “print-on-demand”, also called POD, gets more widespread Native people are starting their own publishing companies to fill the void and control our own stories. Literary advocates say expanding representation for children is vital for strengthening identity and countering harmful narratives early in life.

Poetry collections by Native authors also reflect the overall expansion. Several works published in 2025 feature themes of healing, ceremony, memory and survival. Poetry continues to serve as an accessible space for Indigenous expression, especially for emerging writers and communities revitalizing language and storytelling traditions.

Challenges still exist

Though many celebrate the progress in Indigenous publishing, writers and advocates say challenges remain. Some authors still face pressure to format stories in ways that fit non-Native expectations. Industry support can also be uneven, with marketing budgets often favoring a small number of high-profile books while others struggle for visibility.

There is also concern about ensuring that editing and publication processes respect cultural protocols. Native writers sometimes navigate expectations from publishers around content that touches on cultural knowledge or sacred topics. Advocates emphasize the importance of Indigenous editors, sensitivity readers and cultural consultants who can provide guidance and protect cultural integrity.

Despite the challenges, many in Indian Country say the current publishing environment feels more open and possible than in previous decades. Authors note that for a long time, Native stories were filtered, simplified or erased altogether. The opportunity for Indigenous people to write and publish their own experiences is seen as part of a broader movement for sovereignty, education and empowerment.

Librarians in Native communities say new releases are helping younger readers feel seen and valued. For older readers, especially those whose family histories intersect with traumatic policies like forced relocation or boarding schools, these books offer validation and space for healing. Some tribal programs have begun featuring book clubs and reading circles as part of community wellness initiatives.

The growth in Indigenous nonfiction, especially works tied to policy, history and activism, is being welcomed by Native scholars and organizers. Books that examine issues like water rights, missing and murdered Indigenous women, climate change and treaty recognition are giving readers the means to understand ongoing struggles that news stories often overlook. Writers say that storytelling in these forms can build awareness and support for real-world change.

As 2026 approaches, publishers anticipate that more announcements from Indigenous authors will appear in the coming months. Literary organizations dedicated to Native writers have expanded their support programs, suggesting a continued rise in Indigenous voices entering the publishing world. Book critics say that if current trends continue, Indigenous literature will become a more permanent and prominent part of American reading habits, rather than a short-term spotlight.

Many Indigenous authors express hope that this moment will encourage young writers to pursue their own work. Some say they grew up without seeing Native authors in classrooms or libraries and now want to change that experience for the next generation. Their goal is not only to publish books, but also to build a literary landscape where Indigenous identity is understood as vibrant, diverse and evolving.

As this year’s new releases reach readers and next year’s titles appear on the horizon, Native-authored books are claiming a stronger position in the story of American literature. The shift is not only about artistic achievement, but also about representation and truth. In fiction and nonfiction alike, Indigenous writers are opening doors to stories that have long deserved to be heard.