On the crisp, bright morning of

September 5, dozens of South High School students and staff gathered

together on the football field. After a few moments of brief chatting

and lingering, Robert “Animikii” Horton (Rainy River First

Nations), the new coordinator for the All Nations program, picked up

a microphone to welcome the group.

He greeted the assembly in the Ojibwe

language and asked that they all form a large circle. For the

remainder of the event, Native American students enrolled in the All

Nations program helped to smudge, sing at the drum and pray together

with their tobacco for a good school year.

The All Nations program is a

specialized academic option at South High School that was designed

specifically for Native students. Thoughtful integration of the

Ojibwe culture and language is the foundation for All Nations

academic approach.

The passion to revitalize Native

languages has ignited an internal fire within a growing number of

young adults specifically in Minnesota, where Dakota and Ojibwe are

the original languages. On any given day in Minnesota, fresh-faced

language warriors rise every morning on a mission to reclaim their

languages through education, social media, community gatherings,

apprenticeships and ceremonies. By any means necessary, they have

devoted their lives to Indigenous language acquisition.

Elizabeth Strong, 34, (Anishinaabe)

Coordinator for Language Projects for the Red Lake Economic

Development & Planning reflects on the first time she realized

she wanted to pursue this work, “I visited an immersion school in

Montana. Hearing those young children speaking their own language,

learning about their culture with their elders, it really struck a

chord with me."

From then on, she decided to journey

back home to be a part of the movement in Red Lake. A Head Start

immersion school was launched this year on the Red Lake reservation

as a proactive initiative toward restoring their unique dialect of

Ojibwe. The immersion teachers there work closely to gain knowledge

from a dream team of brilliant elders from the area. They are

focusing on developing curriculum, books, educational materials and

lesson plans to support the immersion experience.

These language advocates all agree

that there is a deep sense of urgency that intensifies with every

passing day as elders carrying priceless wisdom age more and more.

Ethan Neerdaels, Dakota Language

Society executive director, explained, “With a majority of our

speakers being over the age of 65, it is crucial that we focus on the

youth and encourage them to be the next generation of speakers.” He

encourages anyone wanting to learn more about language, history and

culture to take advantage of the opportunity to connect with their

elders. “Visit with them, ask them questions, be a good relative.”

Ojibwe Language professor at Bemidji

State University, Henry “Ginew Giizhik” Flocken, urges anyone

dedicating themselves to learning the language to start with tobacco.

This may seem like a fundamental concept, but for many Native people,

learning their own language is a very spiritual endeavor. As an

emerging elder in his community, the professor explained, “Our

language is a sacred gift from the Creator, we need to cherish and

nurture that gift.”

The spirit of the language is powerful

and a life changing event for students who embrace it as such.

Indigenous Linguist, James “Kaagegaabaw” Vukelich (Turtle

Mountain Ojibwe) shared his experience on his language learning, “The

Ojibwe language is the most elegant and sophisticated system I’ve

ever studied. It is given me the most fascinating view of life.”

He has worked for Minneapolis Indian

Education for over five years, developing Ojibwe language and culture

professional development opportunities for Minneapolis Public Schools

teachers. Most recently, he has created online programs for middle

school students to learn Ojibwe. Vukelich has also helped organize a

family language table, which is a collaboration with Dakota linguist

Neil McKay at Anishinabe Academy that is open to the

community.

This language table also helps

participants to explore having a deeper understanding of the Ojibwe

and Dakota worldview. He strongly believes that these values behave

as a fertile ground for our language to flourish. “Just as manoomin

(wild rice) requires a delicate balance within their ecosystem, our

language also needs an environment to survive in,” he said. “Living

mino-bimaadiziwin with our Grandfather teachings will allow the

language to grow.”

A multi-pronged approach to language

learning also includes living a certain way. Many language advocates

participate in ceremonies, where everything is done only Ojibwe or

Dakota. Flocken feels that he sees a positive shift in the past

twenty years. “It’s now OK to go to ceremony. It is no longer a

taboo. Our people are not afraid to talk about them.” Ceremonies

are also a great place to increase the connection of family. “Now

ceremonies are multi-generational. Kids see their parents learning

and it improves their lives.”

For anyone seriously considering the

journey of learning Indigenous languages, there is a strong network

of language advocates that will be there with you in this important

battle. Professor of Ojibwe at Saint Scholastica in Duluth, Mike

“Migizi” Sullivan strongly believes immersion and language usage

is the ultimate way to becoming fluent. To his fellow language

warriors, he encourages them to “be fearless and constantly reset

your goals.”

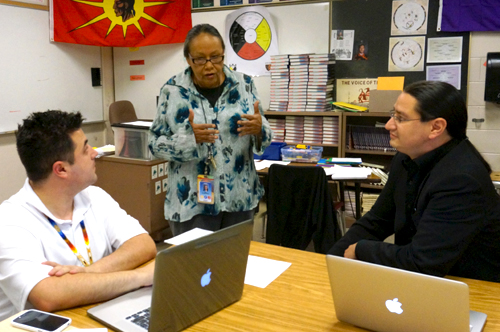

PHOTO:

Robert Horton and James Vukelich connect with Ida Downwin-Bald Eagle at

the South All Nationa Ojibwe language tavle to discuss strategies to

continue teaching Ojibwe both in the school and at home. (Photo by

Breanna Green)