Book review by Deborah Locke

When you read Brenda Child’s “My Grandfather’s Knocking Sticks,” you may ask yourself this question. Why, why didn’t I ask my grandparents and mother and aunties and uncles more about Ojibwe life in Minnesota, and then write it down? Or record it?

Fortunately, Child not only listened to and observed her family members on the Red Lake Reservation, but also did exhaustive research into their working lives and the lives of other Great Lakes American Indians.

The result is this highly readable memoir/historical account of family life and work, and the growing disruptions into each by government policies, the flu, World War I and the Depression. For me, the most insightful and entertaining portions of the book portray the childhood Red Lake village where Child grew up with an assortment of engaging relatives, none of whom feared hard work. Also of interest are the chapters on fishing, ricing and the introduction of the jingle dress, each of which demonstrate the leadership and strength of Ojibwe women.

Grandma Jeanette Jones Auginash was born in 1905 in Ponemah on the Red Lake Reservation. She attended a government boarding school in Flandrau, South Dakota, and met and married Fred Auginash of Sandy Lake who was almost 20 years her senior.

Jeanette mastered the wood stove to become a champion baker of sourdough bread, which pleased her husband. She harvested fish and wild rice, collected and dispensed medicinal herbs from the forest, and went on to sell beer and whiskey. The couple had six children; of the six, four survived. Brenda Child’s mother Florence was born in 1938.

Grandpa Fred Auginash served in the U.S. Army for a short time. He and Jeanette never had much money but did have a good marriage. Fred worked as a logger and at a sawmill, and harvested fish. His years of hard labor were marred irrevocably when he was mistaken for a bear and shot. Fred recovered, but never regained his strength.

Consequently, Jeanette became a fierce conduit between the family and government and reservation relief workers, and went on to outlive her husband by 30 years.

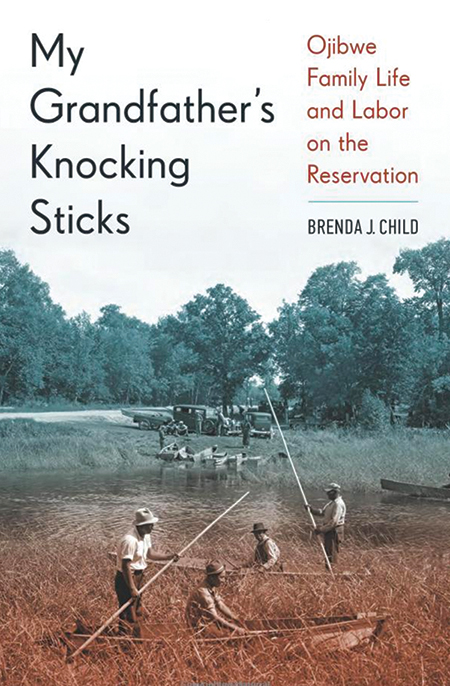

Child’s stories about her grandparents brings them to life so effectively that you feel you know them. Old photos throughout the book may resemble many you have seen of your own reservation families: shy children, reluctant to look at the camera, proud smiling adults in period clothing.

You may also recall older family photos of women collecting the wild rice harvest harvest. That’s because at one time, women exclusively collected and processed the wild rice. They also netted the fish. Children “danced” on the drying rice to remove husks. Child shows labor equality as an important Ojibwe value, as well as the importance of the family unit for survival. Child’s extensive research also shows the gradual influence of national and global developments: World War, a Depression, widespread land loss by both the Ojibwe and Dakota, the influence of unscrupulous Indian agents and the effect of the 1918 flu epidemic.

That epidemic led to the entrance at powwows of the jingle dress initially worn by Ojibwe elders including Jeanette Auginash. Child described the Jingle Dress Dance as a “revolutionary new tradition of healing that appears to have surfaced simultaneously in Ojibwe communities of both the United States and Canada. Women invented new performance rituals as they worked to restore health to those stricken by influenza, at the same time delivering spiritual sustenance to others who lost relatives and loved ones to the deadly disease.”

Special healing songs are still associated with the Jingle Dress Dance, and the women wearing them do so to ensure health and vitality in their families and communities.

Grandpa Fred Auginash’a knocking sticks used during the wild rice harvest serve as a symbol of Ojibwe resiliency and the evolution of work to a system of wage labor. Child once assumed that men led the wild rice harvest because that is the way it occurred while she grew up in the 1960s and 1970s. She was surprised to learn through her scholarship that traditionally, Ojibwe women tended to the harvest and that her own grandfather was among the men who first joined women to bring in the rice.

Illuminations like that one, coupled with the sweet story of family, made this a book to remember.

Brenda Child is an American Studies professor at the University of Minnesota. “My Grandfather’s Knocking Sticks: Ojibwe Family Life and Labor on the Reservation” won the Labriola Center American Indian National Book Award and the Jon Gjerde Prize from the Midwestern History Association.