Review by Deborah Locke

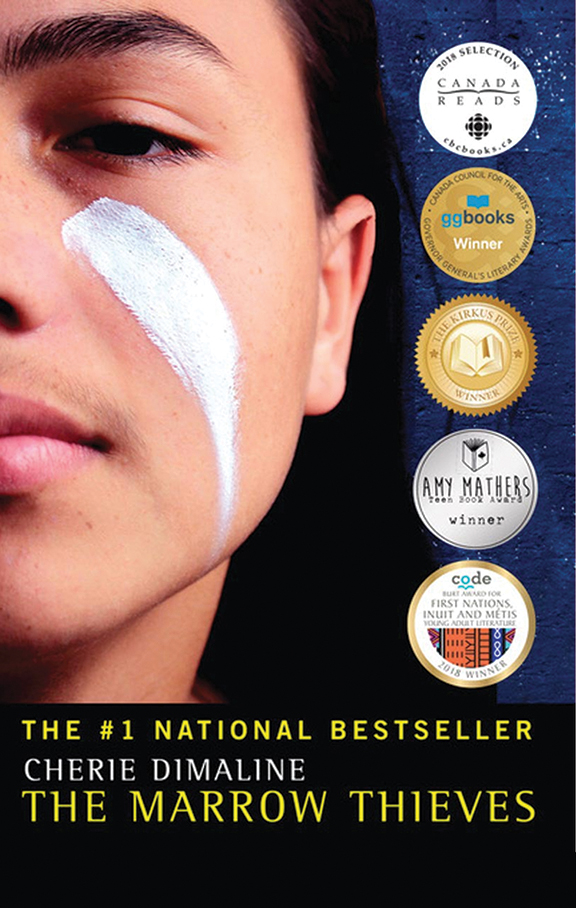

The Marrow Thieves

By Cherie Dimaline

Publisher:DCB (imprint/Cormorant Books)

September 2017

260 pages

Reading age: 13 years and up

Grade level: 8 – 12

One of the first matters to be clear about in “The Marrow Thieves” (by Cherie Dimaline, Metis) is an understanding of dystopia. The futuristic novel is set in a dystopian world of misery, where everything is as bad as it can be, cruelty, bigotry and hardship reign, and life is bleak.

One more point. The young adult novel, aimed at readers age 14 and up, is a family-centered love story. I know what you’re thinking. You’re thinking, “Huh?”

Yes, the book is true to its genre in many ways. It’s hard to read in spots with characters whose behavior make you sick. It’s bizarre. It opens your eyes to horror. It’s a call to action of sorts, pointing out the ways that today’s indifference to climate change and bigotry could lead to tomorrow’s more broken world. And it smacks you across the head with an echo of the past.

The story opens with narration by Frenchie, a 16-year-old Metis Canadian Indian who is running from the “recruiters” who kidnap American Indians, kill them and extract their bone marrow. In this world set in the near future, half the population is dead, and humans can no longer dream which makes them insane. Only Indians dream with aid from their bone marrow, which is where the dreams reside. Recruiters hunt down Indians who are forced into residential “schools” which are really prisons in disguise. The Indians die painful deaths, and their bone marrow is collected in test tubes and distributed.

If that’s not enough, consider this. Into this environment, climate change transformed North America into a hot, waterless, rodent-filled, mangled mess. The very air is unbreathable with dirt and oppression, and clean, drinkable water is a luxury. In fact, water gets a lot of mention in the book as a rare commodity. When the fleeing troupe of Indians finds bottled water in a runover abandoned hotel, they celebrate.

A couple of things here: first, if science fiction spiced with misery and foreshadowing isn’t your thing, skip this book. You will never suspend your disbelief. Second, references to the residential “schools” is a thin veil for the actual residential schools many Indians were forced to attend in the 1800s and 1900s in both Canada and the U.S. One may argue that murder for a bodily substance was never the goal of the public and private operators of those schools, as depicted in “The Marrow Thieves.” However, inquiring minds in both Canada and the U.S. have asked questions recently about the cemeteries filled with children located just outside the public and private residential schools. In this way, the futuristic plot gives a nod to a dark, unspeakable past.

Here’s one more to chew on: the story centers on desperate Indians fleeing for their lives through overrun forests. Fact or fiction? Just consider Minnesota history. Think of the Dakota in Minnesota in the 1860s, running for their lives after being banished from the state with a price on their heads. Some fled to Canada, walking all the way at night to avoid capture. Care to learn more? Check online for the Minnesota Historical Society website about the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862.

Whoops, perhaps I digress.

So, dear reader, read Dimaline’s book about the way strong ties may be forged under fire, and about the way boys and girls fall in love, and about traitorous, sell-out Indians, and about courage and respect for elders, and about a world that seems so absurdly fictional.

Or is it?

A few of the awards this book received include the Governor General’s Literary Award, the Kirkus Prize, the Sunburst Award and the Amy Mathers Teen Book Award.