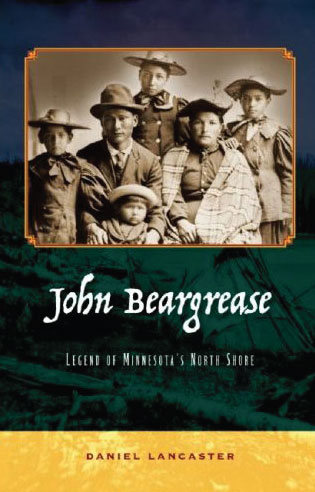

Many people know the quick version of the John Beargrease story: The son of an Ojibwe chief who grew up on the rugged North Shore in the 1850s, he started delivering mail by boat, dogsled and foot – and didn’t let up for two decades.

Many people know the quick version of the John Beargrease story: The son of an Ojibwe chief who grew up on the rugged North Shore in the 1850s, he started delivering mail by boat, dogsled and foot – and didn’t let up for two decades.

Daniel Lancaster, an editor from Minneapolis who keeps a vacation home near Silver Bay, wanted to know more. He was thinking about writing a piece of historical fiction based on Beargrease’s life, and went looking for a definitive work on the namesake of the annual Northeastern Minnesota sleddog marathon. To his surprise, there was none, and thus began Lancaster’s obsession.

He began combing through turn-of-the-century newspaper clippings, correspondence from the Bois Forte Band of Lake Superior Chippewa archives, even the single remaining volume of records from a state mental institution that operated in Fergus Falls, Minn.

What emerged was his new book, “John Beargrease: Legend of Minnesota’s North Shore,” a portrait of Beargrease as one of the “usual heroes” who lived and worked along the edge of Lake Superior

He and his brothers delivered mail for nearly two decades, providing one of the only links to the outside world for the tiny but growing communities. In winter, Beargrease’s arrival in Beaver Bay, Lutsen or Lax Lake was heralded by the jingling bells strung

to his sled dogs’ harnesses. People would gather around to greet him, reach for their mail and ask for news from up and down the shore, and soon enough Beargrease would be off again to finish the two-day trip between Two Harbors and Grand Marais. “Everyone was a hero in those days,” Lancaster said. “He was one of many North Shore mail carriers that performed these amazing feats.”

So why did Beargrease became a legend, but fellow mail carrier Louis Plante, who also relayed mail up and down the shore, did not? Lancaster thinks it might be because Beargrease was a sociable man who left a strong impression. “He made a lot of friends, so people just remembered him,” Lancaster said. Lancaster said Beargrease also was “standing at the crossroads between modern America and the old world.”

“His story is so connected with the settlement and development of the North Shore, and the great loss the Ojibwe suffered,” Lancaster said. “His generation saw that transition. To me, Beargrease was unique in that he successfully lived in both worlds.”Exploring how the American Indian community fared during Beargrease’s time was intriguing to Jim Perlman, editor and publisher of Holy Cow! Press in Duluth.

Lancaster’s history “presents the almost uncomfortable relationships between the white settlers and the Indians who were here beforehand,” Perlman said. “That’s sanitized in other history books.”One great loss, Lancaster said, was the lack of oral history from

Beargrease’s descendants. That was the result of the government- imposed Indian boarding school era, where childrenwere forcibly divorced from their parents and their own culture, cutting off the oral traditions that would have kept alive more stories of Beargrease’s exploits.

After retiring in 1899, Beargrease made his home in Beaver Bay and Grand Portage. He died in 1910 after leaping into Lake Superior’s frigid water to save another mail carrier. Both men emerged from the lake, but Beargrease contracted pneumonia and died months later, at the approximate age of 48.

“The work he accepted he performed under harsh conditions,” Perlman said. “He required ingenuity and fortitude to carry out his missions.” Today, thousands of people gather each year to cheer teams competing in the John Beargrease Sled Dog Marathon along the North Shore, and the first musher to leave the starting gate is always the ghost of John Beargrease. The fanfare might urprise the man who became a legend, Lancaster said.

“He was a private citizen,” Lancaster said. “He would certainly be astounded that he is remembered and celebrated to this day.”