By Lee Egerstrom

A new book about Ho-Chunk experiences in Minnesota should prove once and for all that “Minnesota Nice” does not describe the state’s historic relationship with its Indigenous populations. Or any other state’s, or the nation’s, for that matter.

Cathy Coats, a metadata specialist who works on cataloging research documents at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities campuses, has written a new book on Ho-Chunk tribal experiences in Minnesota.

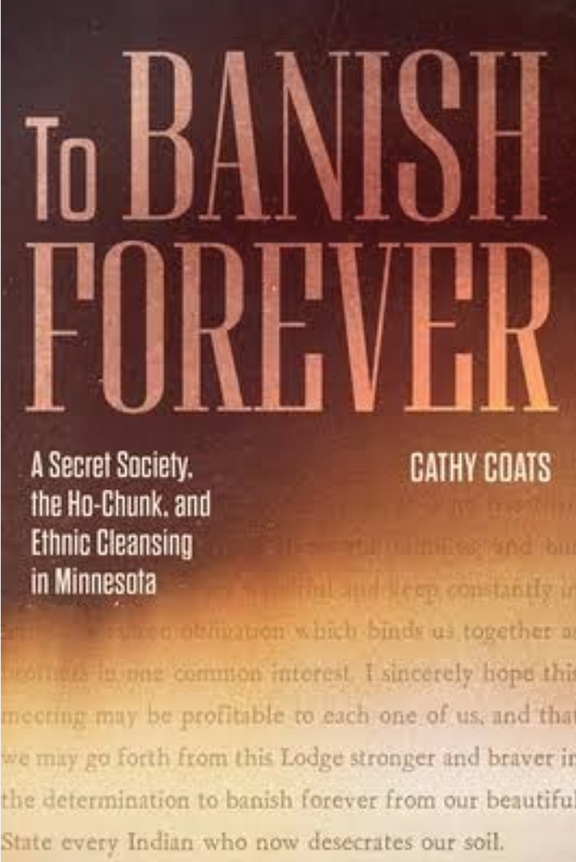

To Banish Forever: A Secret Society, the Ho-Chunk, and Ethnic Cleansing in Minnesota was published in January by Minnesota Historical Society Press. The book was launched at All My Relations Gallery in Minneapolis on Jan. 17. The following night Coats and friends presented the book at a Ho-Chunk regional meeting in St. Paul.

Ho-Chunk experiences are documented in various government reports, old newspaper articles, and in academic work that Coats accessed for her book. It includes Ho-Chunk interaction with a Minnesota-based hate group not all Minnesotans will want to know about, but should. That she and other researchers have found these links shows how unpleasant history sometimes hide in plain sight.

Such history isn’t often taught in schools. “What Ho-Chunk know about this is handed down from family experiences. Most Minnesotans don’t know any of it,” Coats said.

She discovered it in passing by reading a reference to it in Last Woman Standing, a 1981 fiction book by White Earth Nation’s Winona LaDuke. Coats was an undergraduate student at St. Cloud State University and it prompted the history-minded research student to dig further.

That continued into graduate school where her graduate advisor was Mary Lethert Wingerd, a SCSU history professor and prominent Minnesota historian, an experts on the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862 and author of North Country: The Making of Minnesota.

Reception

At All My Relations Gallery, Ho-Chunk Tribal Historic Preservation Officer Bill Quackenbush from the Black River Falls tribal headquarters joined with Minnesota Ho-Chunk leader Robert Pilot and University of California Santa Cruz professor and author Amy Lonetree in presenting Coats a blanket depicting the Ho-Chunk flag.

Ceremonies using blankets and the giving of blankets are wrapped in nearly all tribal cultures through the Americas. “It was emotional, for me,” Coats said.

Ho-Chunk from Minnesota, Wisconsin and elsewhere are thanking her for writing this book “in plain language so you don’t have to be an academic to understand it.” That should also help all Minnesotans connect with their own and their shared histories.

Key takeaways from Coats’ book

Efforts to banish the Ho-Chunk from Wisconsin pushed many to live along the Mississippi River in southeastern Minnesota and adjacent areas of Iowa, thus giving the latter’s college town of Decorah its name. That became the first of five major movements forced on Ho-Chunk from poor, to fertile, to extremely unproductive, to eventually to passable land settings.

After moving from the Mississippi River banks, the Ho-Chunk settled at a short-lived reservation in a mostly wooded area around Long Prairie not suitable for their food production. Next stop was the desired, fertile land in what is now Blue Earth and Steele counties south of Mankato.

It was there that ethnic cleansing activities teamed with land speculation interests to produce an ugly and, until now, mostly hidden episode of Minnesota history. When movers and shakers at Mankato and some surrounding communities became aware of the fertile ground the Ho-Chunk inhabited, they started a huge political campaign to get state officials and Congress to move the Ho-Chunk again, or “to banish forever” from the state.

Those efforts had local terrorist support. Some Southern Minnesota movers and shakers formed a secret society call the Knights of the Forest. For a period of time, they posted guards camped around the Ho-Chunk reservation with instructions to shoot any Indians who crossed over the boundary lines.

Their political effort succeeded and was aided by Minnesota fears Ho-Chunk might join forces with nearby Dakota warriors during the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862. Violence played a part as the Ho-Chunk were moved at gunpoint from the fertile lands near Mankato to desolate, unproductive land at Crow Creek, along the Missouri River in what became South Dakota. That instant failure of resettlement prompted another movement to shared reservation land in Nebraska.

Connections of the current with the past

The Knights of the Forest were a contemporary of the Ku Klux Klan, but not a product of that hate group’s movement. Coats puts their goals and timing in perspective. All various “knights” movements had ties to secret and fraternal organizations popular within Nineteenth Century society.

The Minnesota Knights group was more like the Texas Rangers. The latter’s origins can also be traced to white settler efforts to remove Indigenous tribes from the Lone Star state. Thus, Minnesota baseball fans have even more reason to like their “Twins.”

Land speculators were the driving force behind Ho-Chunk removal efforts in Minnesota. Coats shows this clearly and notes fortunes were made by disposing Ho-Chunk and selling their land to new settlers.

Minnesota history lovers should be aware this wasn’t the only time property theft was masked behind public safety sounding rhetoric. A great historian at Augsburg College, Carl H. Chrislock, exposed how history was repeated when well-connected people teamed with pompous politicians to “protect” all from German-American farmers during World War I.

Watchdog of Loyalty: The Minnesota Commission of Public Safety During World War I, was published by Minnesota Historical Society Press in 1991. Again, according to legend in west-central and southern Minnesota, new fortunes was made recycling former Native lands again being taken from German-American farmers.

Chrislock’s book showed how farmers not German Americans were also harmed and driven out of the state at that time for holding political views not shared by the state’s political power trust.

Ho-Chunks still call Minnesota

Resilient Ho-Chunks still call Minnesota home despite state and national laws and removal actions that have been amended, eliminated or at least no longer enforced. That said, most promises to Ho-Chunk groups in treaties were never fulfilled. Land promised in Minnesota was not restored.

More than 1,000 Ho-Chunks continue to live in Minnesota. In a tongue-in-cheek comment on those leftover and ignored laws, local Ho-Chunk leader Robert Pilot told The Circle, “I’m a criminal. I’m not supposed to be here.”

Regardless, he represents Minnesotan Ho-Chunk members in what the Ho-Chunk Nation regards as District 4 – people living outside Wisconsin. Pilot is a broadcaster on Native Roots Radio (am950), is an educator and a Native American civil rights activist.

Current global, national and local Minnesota events make the Coats book on the Ho-Chunk extremely timely.

Forced removals of Indigenous people continue with much bloodshed and starvation in parts of the Middle East, eastern Asia and in Africa; conquest of extremely fertile land is an objective behind an occupation attempt in Ukraine. Motives for these actions resonate with Minnesota history.

Long delayed remedial actions are taking place in Minnesota and around the U.S., however. Here at home, the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources will close the Upper Sioux Agency State Park on Feb. 16 and will return the land to the Upper Sioux Community.

This action, approved by the Minnesota Legislature in the past session, was long requested by the Dakota tribes. The DNR noted in its announcement, “This land is the site of starvation and death of Dakota people during the summer of 1982, when the U.S. Government failed to provide food promised to the Dakota by treaty.”

Also, the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, Chicago’s Field Museum, the Cleveland Museum of Art and the Denver Museum of Nature and Science have eliminated exhibits or have closed some for revamping how Native artifacts and cultures are displayed. This comes in response to tribal objections to past displays and requests for repatriation of human remains and artifacts, supported by the Biden Administration.

Strong support for these museum efforts came from Lonetree, the American Studies professor at UC Santa Cruz who was part of Coats’ book launch presentations. She is author of a 2012 book, Decolonizing Museums: Representing Native Americans in National and Tribal Museums; and co-author of a book on the Ho-Chunk Nation, People of the Big Voice: Photographs of Ho-Chunk Families by Charles Van Schaick, 1879-1942.

Details on future book events will be posted at the Minnesota Historical Society Press website https://www.mnhs.org/mnhspress.

A Minneapolis Star Tribune article about Coats’ master’s thesis at St. Cloud State University that lead to the book was published in 2018. It is accessible at https://www.startribune.com/secret-hate-group-bent-on-banishing-ho-chunk-indians-in-1863/475744423.