By Dan Kraker/MPR News

Medical student Fred Blaisdell has a few months to go before anyone calls him doctor, but the Oneida Nation tribal member has already learned one lesson around the importance of Native physicians serving Native patients. During a recent psychiatry rotation at a Minneapolis clinic, he introduced himself to a patient who lit up when she heard him speak Ojibwe.

“After that, the patient really opened up and started to talk about a lot more things that she hadn’t really engaged with us before,” recalled Blaisdell, 27, who’s from the Detroit area but chose the University of Minnesota’s medical school in Duluth for its national reputation training doctors from Native populations.

School leaders say the need for doctors like Blaisdell is huge and growing in an era of COVID-19 and other health worries. It’s led the university to launch a new effort to boost the number of Native physicians and other care workers in Minnesota and across the country.

Last year, nearly 21,000 students graduated from medical schools in the United States. Only 160 of those new doctors – fewer than 1 percent – were Native American.

“It’s not just physicians, right? We don’t have enough Native PAs (physician assistants). We don’t have enough Native nurses. We don’t have enough Native pharmacists,” said Dr. Mary Owen, director of the U’s Center of American Indian and Minority Health. “We tend to work in teams, so it’s hugely important that we develop all these different health professions.”

‘I talk to newborn babies about medical school’

Owen and others seeking to recruit Native students for medical schools say part of the challenge is to create better pathways between two-year tribal colleges and four-year institutions.

“Students have a history of feeling like the university isn’t for them. They doubt that jobs are for them, because they don’t see themselves in careers,” said Anna Fellegy, vice president for academic affairs at Fond du Lac Tribal and Community College in Cloquet, Minn.

“And so it takes a different type of service to [get] the students to just allay some of that fear,” she said, “take the mystery out of processes and get the ground firmly underneath their feet.”

The work also needs to start much earlier. In Minnesota, only about 56 percent of Native high school students graduate in four years.

Dr. Arne Vainio, a member of the Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe who has practiced on the Fond du Lac reservation for the past 24 years, said he’s always encouraged young people to pursue careers in medicine but now he starts even earlier.

“I talk to newborn babies about medical school,” he said. “The parents always listen. But I make sure that I’m talking directly to the baby about that. And, you know, let them know they have options. And then when they come in for visits, we talk about that again.”

When young people see him, a Native American doctor, it allows them to envision themselves in the same position, he said, adding that when he was a little kid, a lot of the Native men he saw were truckers. “And that’s all I wanted to be.”

He credits a group of people who always encouraged him and held him accountable. “They’re the ones that derailed my dream of being a truck driver, and I ended up in medical school instead.”

Growing doctors close to home

Owen, 56, said her journey to become a physician began when she was a patient at the Alaska Native Medical Center in Anchorage, in the late 1980s. “I didn’t see any Native doctors or even Native nurses at that time,” she recalled.

A member of the Tlingit Nation in Alaska, Owen said that played a role in pushing her to go to medical school. “That anger propelled me, actually – anger at our lack of representation.”

She went on to earn her medical degree from the University of Minnesota. She then returned to Alaska to serve her tribal community. She came back to the University of Minnesota in 2014 in part to address the same issue she recognized 30 years ago.

Last year, Owen assembled hundreds of Native American health professionals for a summit on the issue. That led to the creation of regional hubs that are working to grow the number of Native health care professionals in specific areas around the country.

That’s critical because some areas have more severe shortages than others. For example, she says Indian Health Service facilities in the Upper Midwest have a nearly 50 percent vacancy rate for physicians.

“I think if we can grow, if we can get more Native students from this area, through school, into practice, they’re more likely to serve and stay in this area,” said Owen, who’s also board president of the Association of American Indian Physicians. “We know that Native students like to go to school in areas closer to their homes.”

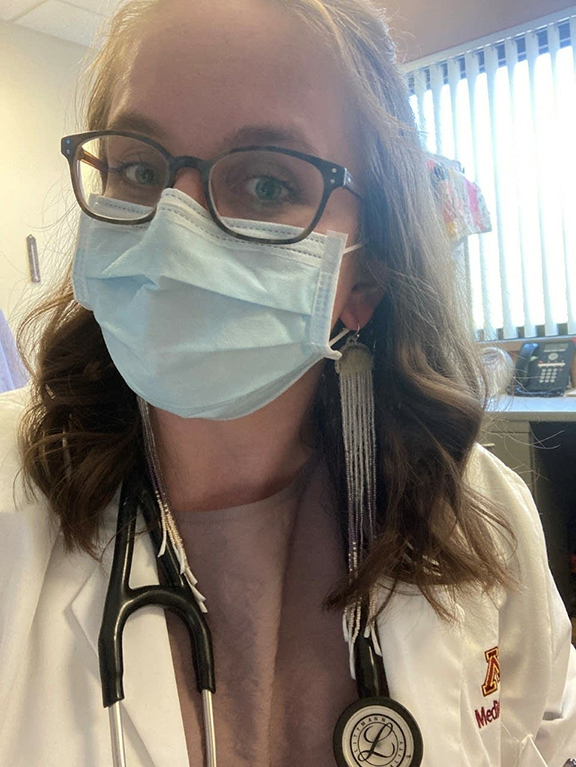

That includes University of Minnesota medical student Genevieve Bern, who counts Vainio as a mentor. Watching how he interacts with his young patients has inspired her to also encourage young patients to pursue careers in health care.

“That’s something that I hope someday I’ll be able to have those conversations with Native youth,” she said.

Bern, 28, grew up in Worthington, Minn. She’s Native Alaskan, but she said her culture wasn’t a big part of her childhood growing up. She’s since enrolled in her tribe and started to learn the language, and when she graduates, she plans to work in some way with Native people.

“It’s part of who I am,” she said, “and it just has always felt like it’s like what I’m supposed to give to my community.”