By Ava Kian/MinnPost

Wayne Dupuis remembers a time when he was hunting with his father on the Fond du Lac Indian Reservation and came upon the University of Minnesota’s Forestry Center, which sits on reservation land.

Dupuis hesitated, not sure if the two could be there. “I was under 10-years-old and my dad (and I), we were hunting over here … and he said, ‘Yeah, we’re gonna go hunting in there,” he recalled. “They don’t allow us to but we’re gonna go hunting in there anyway because that’s our right. This is our reservation. This is our homeland.’”

Dupuis was one of several people who weighed in Tuesday at a listening session in Cloquet over the future of the land and the forestry center, which the university plans to return to the Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa. The hearing in the center’s auditorium drew nearly a hundred people who came from Duluth, the reservation and areas of Carlton County.

The university’s decision emerged out of conversations with the tribe, said Karen Diver, the school’s senior advisor to the president for Native American affairs.

Emotions were mixed among the people in the crowd. Some expressed disdain with the university’s choice – specifically mentioning a lack of transparency from the university. Others, like Dupuis, were happy that the university is taking this step.

“We have 100,000 acres that’s been been marked as our homeland,” Dupuis said in reference to the reservation. “This, what you call institution, we call our homeland, is 3% of our home base. You think about millions of acres that we ceded away, and a way of life that we give up.”

A century old research center

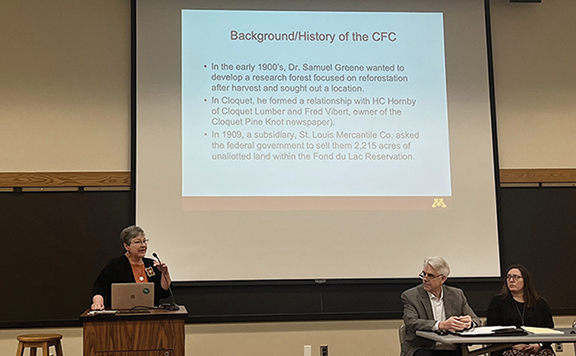

The University of Minnesota is what critics refer to as a “land grab” institution, meaning that portions of it sit on areas that previously belonged to some of the state’s tribes, like the land of the Cloquet Forestry Center, located about a two-hours drive north of the Twin Cities.

The land was originally set aside by the federal government for the band as part of the La Pointe Treaty of 1854. But federal law allowed the U.S. government to transfer “unallotted” Fond du Lac land to lumber companies for logging, with the understanding that it would go to the university afterward.

In 1909, the Cloquet Forestry Center was established on 2,000 acres. The center continued to expand until 2003 and is currently 3,400 acres. It lies completely within the boundaries of the tribal reservation.

In recent years, the university has been coming to terms with its history as an institution that has benefitted from tribal land.

In 2021, Diver, a former Fond du Lac tribal chairwoman and Obama administration Native American affairs adviser, was hired to strengthen relationships with Minnesota’s tribal nations. She said that in her time as a tribal leader, which ended in 2015, she had asked to get the land back.

In 2020, the Minnesota Indian Affairs Council – a governing body that includes tribal chairs from 10 of the state’s 11 tribes – passed a resolution asking for the return of the land.

Diver said that when former University president Joan Gabel began in her position, she started meeting with tribal nations more regularly, around three times a year. She said that the forestry center frequently came up in those conversations.

In February 2023, Gabel recommended to the Board of Regents that the university begin the process of returning the land to the band.

The center is not the only university-owned area in the state that previously belonged to tribes. When President Abraham Lincoln signed the Morrill Act in 1862, large sums of Indigenous lands in the nation were turned into endowments for colleges and universities. In Minnesota, those areas span across 22 counties.

Diver said the return of this particular land is unique and won’t set a precedent for other areas because the land is “wholly within the borders of a tribal community.”

A new report by the non-profit media outlet Grist shows that since the university’s inception, nearly 187,000 acres of land have been acquired from the tribes and that much of the land has been profitable. The report shows that between 2018 and 2022, the University of Minnesota earned nearly $17.2 million in mineral revenues from the land obtained from the tribes.

The forestry center has become a hub of knowledge and education. At the listening session, former students and faculty — some dating to the 1970s — shared what the center means to the forestry profession.

What’s so special about the center?

The center, located three miles west of Cloquet in Carlton County, has been the primary research and education forest for the University of Minnesota. At the meeting, people talked about how well known it is in the industry.

The center includes large swaths of pine trees – some dating to the 1820s, the local Pine Knot News wrote. It’s also been a place for various educational and research projects that have explored wildlife populations and habitats, forest genetics, ecology, entomology, plant pathology and hydrology, as well as the effects of climate change on forest productivity, among other topics.

More than a handful of people at the listening session expressed how important the center has been for research purposes.

“I’m not sure if you or the Board of Regents have any idea how important this decision is to the University of Minnesota, the state and the people,” said Al Alm, a former faculty member at the center, to Brian Buhr, the dean of the university’s College of Food, Agricultural and Natural Resource Science.

Alm recalled an ecology professor in China asking him if he knew anything about the forestry center in Minnesota. To him, and many others, it’s globally known. Several others expressed worries about losing the educational value that the forestry center brought to the area.

A common theme among people was that they don’t want the research to end — and want the university to find a way to stay involved.

“This seems like a perfect place for where the reservation has interest and the university has an interest. They seem like they overlap, where both have an interest in the environment and proceeding as we have it now and clean air and teaching the future generations of what can be accomplished and what needs to be done together,” said Steve Korby, a Cloquet resident.

At the end of the meeting, Buhr said the university does not plan to gut its forestry research program.

“We have no intention of stopping forest resources, “Buhr said. “We intend to keep that moving forward in a successful way and finding ways to do that regardless of what happens here.”

Returning the land

Josyaah Budreau, a researcher at the University of Minnesota-Duluth and a member of the band, said that while research is important, the return of the land is necessary.

“There’s been a lot of talk about the history of this institution and such,” he said. “It doesn’t reflect the history of this place … that this community has had to historically deal with and that this land also has history to the people that were here beforehand,” he said. “I agree that it (research) needs to continue to be done, but why is it always at the expense of tribal communities — of these communities that have predated these institutions?”

Dupuis, who lives near the area, said that while the land benefited businesses and those getting an education in forestry, it completely excluded the tribe right next door.

“It was an incubation for many of the businesses that have grown from here. But for many, many years, you didn’t see anything happening for Fond du Lac,” he said. “That wasn’t the focus.”

There was some interest from people in the crowd for the university to partner with the tribe. In response to those comments, many people shared ways the band has cared for their land.

“Trust the Fond du Lac band. They care deeply about this place, too, just as you do and they know this place. They know their homeland,” said Carl Sack, a teacher at Fond du Lac Tribal and Community College. “And they do great science, and they have shown a willingness to work with, not against, the current institution.”

A member of the band talked about the care his people have shown the land — and how it is embedded in their teachings.

“When we do get the land back, we will take good care of it. Our rice lakes are proof of that. We have some of the best rice rice lakes in the area, and we have proven that we can take care of our land and we continue to do so,” said Charles Smith, the tribe’s Ojibwe language program coordinator.

The university said it is seeking alternative locations for a forestry center, but the tribe has come to an agreement to facilitate some of the University’s ongoing research. The extent and duration of this agreement are still being discussed, Diver said.

There was interest among many people — both those who were happy and unhappy with the university’s decision — for the university and tribe to work together.

“I hope we do this in the right way, too. I think that there’s ways that we can partner. But this is our homeland; it isn’t your institution,” Dupuis said.