By Arne Vainio, MD

Editor’s note: this article was oringally published in 2016.

We were at the graduation ceremony for the Harbor City International School in Duluth, Minnesota and the commencement address was by Gaelynn Lea Tressler. She is the winner of the 2016 National Public Radio Tiny Desk Concert series and she knows about and exemplifies overcoming hardships and truly appreciating the things we take for granted. She is beautiful and eloquent and she speaks from a position only she can speak from. She sings and she plays her violin from somewhere deep in her soul. She talked to the graduating high school seniors and she talked to our son and she reminded them to always enrich their own lives and to enrich the lives of others. She talked to them of pursuing their dreams and never giving up. She played her violin and she sang to them and the crowd was speechless and the auditorium was silent as her last notes were fading. This is an excerpt from her NPR Tiny Desk concert performance. Please don’t pass it up, this is five minutes and six seconds you will never regret.

You have time to watch this: Gaelynn Lea Tressler YouTube Video Clip at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n6oSeODGmoQ.

I was thinking about our son in this context when I was asked to be the keynote speaker for the University of Minnesota Medical School Native American graduates a few weeks ago. There were six graduates, and while it seems that is not very many, these are very important graduates. They are important to their families and important to their tribes and important to their communities. Major life transitions should always carry ceremonies.

There was a time when our people celebrated times of change and advancing to the next stage of life. Maybe some still do this, but it didn’t happen for me. I don’t really even know when I became a man. Was it the first time I drove a car? Was it the first time I crashed a car?

There are only a little over 300 members in the Association of American Indian Physicians (AAIP) and six more will be welcome. I spoke to the graduates as a representative of AAIP and I spoke to them as a representative of the University of Minnesota Medical School. I spoke to them as a representative of the Seattle Indian Health Board and I spoke to them as a physician practicing on the Fond du Lac reservation.

I spoke to them as someone who came from and still remembers poverty.

These new physicians have already seen death and they’ve already seen new life. But only from the sidelines.

I had the graduates stand and I gave them all asemaa (sacred tobacco) that I made from the inner bark of red willow. I told them how I made it and I told them I stay up late at night making it because only then can I be alone with my thoughts. I told them I make it exactly the way I was taught and that the one who taught me told me a story as we were making it the first time:

He was a sniper in Vietnam and his job was to do as he was instructed. There was a woman in a village who was organizing people in a way that was not welcome. He watched her for a long time that morning from a great distance. Her children were playing in the dirt yard and there were pigs and dogs and chickens running around. He watched her washing her face in a white enamel basin with a red stripe around the rim. She splashed the water on her face with both hands and she flipped her head back and her long black hair arched over her head with water flying from it and that’s when he pulled the trigger.

She died with her children around her. That was over forty years ago and he hasn’t slept since.

I always think of him and I think of her when I make my asemaa and I think of them when I offer it and when I give it away. We give tobacco when we ask something important of someone or when we want answers or healing or if we wish to honor someone.

I had the graduates stand and I walked through the assembled crowd and among their families and I put asemaa into the hands of each of the graduates and I had them remain standing.

“I ask you in front of your families and your teachers and your elders to take care of our communities. Take care of our babies and take care of our elders and our grandparents. Take care of our addicted and our imprisoned and those less fortunate. You have joined the most ethical and respected profession there is and you need to honor that in your work, but you also need to honor it in your home and community life. Others will look up to you and look to you for guidance and you need to have a pure heart to provide that guidance. This is a transition point and this asemaa means you have left your old life behind. As you travel from this point forward, you will be the ones families will turn to and there will be a sacred and unspoken pact between you and those families. You need to honor that pact.”

I was the first one to hold this brand new baby not so long ago. He has an uphill battle in front of him.

I put my thumbprint on his foot and I whispered into his ear…

“We need you to be strong. We need you to listen to your elders. We need you to learn our songs and our stories. We need you to be a healer. When that time comes, you come and talk to me.

I’ll be waiting for you.”

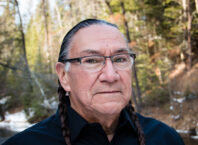

Arne Vainio, M.D. is an enrolled member of the Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe and is a family practice physician on the Fond du Lac reservation in Cloquet, Minnesota. He can be contacted at a-vainio@hotmail.com.