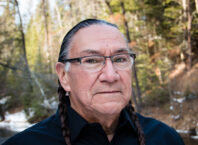

By Arne Vainio

He was nearing death. This moment was inevitable and he hadn’t eaten anything in the past ten days. Three days ago he started refusing water and he was intermittently awake at any time of the night or day. He had fought his cancer for as long as he could and decided to stop chemotherapy when it was making him too sick to be present for his family.

I went to visit him before that time and he was thin and weak and his voice was soft. I had to sit close to him and wasn’t sure if he was always aware of my presence. He reached for my hand and held it and it seemed like he was back asleep. He opened his eyes and he smiled at me. “I see spirits all around me now. They come and they talk to me and they tell me things. You keep doing what you’re doing and thank you for coming to see me.”

I wanted to see him again and it was weeks before my wife Ivy and I could make that long drive. He died before we could get there and the funeral home had already come to get him. We sat with his wife and his family and she told us, “He was talking when he was asleep and when he would wake up he would tell me who he was talking to. Some were people he knew when he was a young man. One of them had your last name and he killed himself a long time ago and he wasn’t very old.”

My father committed suicide when I was four years old. He was forty-two when he died.

I don’t need reminders to think about my father and his suicide and I’ve been thinking about him often since then. George Earth and his mother and father were living in a shack in the summer of 1957. His mother mostly stayed in the shack and cooked and picked berries and gathered what she could. George and his father ran chainsaws and cut and limbed trees all day.

The summers were hot and the mosquitos were vicious and the dust from the skidders dragging trees out of the woods hung thick in the air. They didn’t have ear protection or safety glasses or insect spray and the chain saw smoke kept them in an acrid, choking cloud. In the winter they froze as they cut and they ran for the shack when they got too cold. They didn’t get paid by the hour, they were paid “by the stick” and the trees they cut were counted and kept track of and they each earned less than forty dollars a week.

George introduced my parents to each other. My father was running a tavern called the Good Luck and he was good to George and his family. Sometime after my parents were married, George’s mom was walking along the side of the road and someone ran over her and killed her. Her death wasn’t investigated because she was Ojibwe. No one offered to look into it and George and his father knew better than to ask. The bar business wasn’t good and my father committed suicide that same summer.

George and his father left after that and I didn’t see him again until almost forty years later. As soon as we met we were family again. George came to stay with us as often as he could and we talked on the phone all the time. Sometimes I would call him when I was looking at the stars and listening to the wind and the sounds of the night. Every time I traveled to the ocean, I would call him when my feet were in the water and I would hold my phone out so he could listen to the ocean birds and hear the crashing of the waves and we would put asemaa out together at those times.

I wanted George to travel with me to conferences so he could be with professionals to learn from them, but more importantly, to teach them. He had a gift for humor and a gift for humility, but he was also a vast wealth of traditional knowledge and he could see right to the heart of most matters. He started to get short of breath and he was diagnosed with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. This is a condition with no cure and no known cause and it causes progressive scarring of the lungs and he eventually had a hard time breathing at all. He passed his dance regalia to me at a traditional powwow and I danced as he sat at one of the drums.

The last time I saw him he brought me a guitar he used to play in his youth. He was so short of breath he didn’t even get out of the passenger side of the van. He had me take the guitar case from the back seat and open it on the ground next to him. I flipped the rusty metal buckles on the cardboard case and inside was an old guitar with strings that didn’t match. It was clear it hadn’t been played in a very long time. “I played everything from Merle Haggard to Johnny Cash on that guitar back when I was drinking and it sure made a lot of people happy.”

Our phone conversations changed and I think George was seeing spirits in his final days. I had collected spring water at sunrise on Easter Sunday and my mother used to do that when I was growing up. We drank it as regular water and she cooked with it, but she saved some to use when we were sick. I told George how I collected that water and he said, “I want you to spill some of that water on the ground at my funeral. Will you do that for me?”

I didn’t want to talk about that and I didn’t want him talking like that, but he made me promise and I did that when he died.

Every morning I go outside and I offer my asemaa to the four directions, to the water and to the earth and to the sky. I thank the spirits who watch over us and protect us. I bring my coffee with me and I offer the first drink of coffee to them and I spill some on the ground.

I think of George and I say good morning to him. I think of Leonard and my brother Kelly and my aunt Emma and my mother and my grandparents and my sister Shelly and all of my teachers who have gone before me. We come into this world through a doorway and travel this circle and hopefully make it through all four stages of life before we cross that threshold again. We are told the very young and the very old hold hands across that doorway. No one spends more time closer to it than doctors and nurses and all those who care for those most vulnerable. We see birth and we see death and we see everything in between.

Someday we will all make that journey and what we give of ourselves will be what remains.

I do not see spirits.

Someday, I will.

Arne Vainio, M.D. is an enrolled member of the Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe and is a family practice physician on the Fond du Lac reservation in Cloquet, Minnesota. He can be contacted at a-vainio@hotmail.com.