By Deborah Locke

For students of American Indian history in general – and of niche Ojibwe history in particular – “A Bag Worth a Pony” is for you. Or if you’re a fabric and textile wonk or College of Design instructor or student at the University of Minnesota, “A Bag Worth a Pony” is for you. Or if Ojibwe family names like Kegg, Sam, LeGarde, Hole in the Day, LaFave, Moos, Benjamin, Posey, King, Smith, and a dozen others mean something to you, read this book.

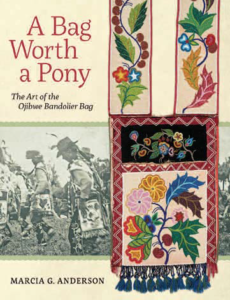

“A Bag Worth A Pony: The Art of the Ojibwe Bandolier Bag” is a meticulous and exceptionally well-illustrated study of the history of beaded Ojibwe bandolier bags, or gashk-ibidaaganag (which loosely translates in Ojibwe as an item that is enclosed, attached and tied).

“A Bag Worth A Pony: The Art of the Ojibwe Bandolier Bag” is a meticulous and exceptionally well-illustrated study of the history of beaded Ojibwe bandolier bags, or gashk-ibidaaganag (which loosely translates in Ojibwe as an item that is enclosed, attached and tied).

The author, Marcia G. Anderson, is a retired collections curator at the Minnesota Historical Society (MHS) who stumbled over a storage box of beaded bags in 1981. The discovery whetted Anderson’s fascination for fabric, crafts and women’s work and presented challenging questions. Who were the women who created the exquisitely beautiful designs? What were the bags used for and for whom were they created? How old are the earliest bags? Why status did they confer to the wearer?

Those questions and more prompted countless trips to museums, archives and Ojibwe reservations to learn the history and artistry of the prestigious gashk-ibidaaganag.

In the first half of the book Anderson’s findings give a tremendous amount of detail about the evolution of the form, structure and motif of the bags. The book’s title is explained here – in the 1800s the Dakota found the Ojibwe gashkibidaaganag so valuable that they traded a pony for an bag. Hence the bags that appear to be dated back to about 1870 – became a form of commerce and of cultural identity, Anderson wrote. Even if the Ojibwe dressed like “Christianized Indian farmers,” the addition of a bag over that clothing was symbolic to Indians and non-Indians of a proud Ojibwe heritage.

The sheer volume of information gives the first half of the book a textbook-like feel. Anderson goes into detail on bead types, thread types, border differences, tassels, fringes, and the disappearance of pockets.

You can easily imagine Anderson with gloved hands cautiously exploring the size and details of all 123 full bags in the MHS collection, and then the dozens of bags she examined off-site. The Society’s photo collection enhanced the study of gashkibidaaganag for Anderson as she ably identified the earlier loom-woven bags and their evolution to the later year spot-stitch applique bags.

You can easily imagine Anderson with gloved hands cautiously exploring the size and details of all 123 full bags in the MHS collection, and then the dozens of bags she examined off-site. The Society’s photo collection enhanced the study of gashkibidaaganag for Anderson as she ably identified the earlier loom-woven bags and their evolution to the later year spot-stitch applique bags.

In the book’s photos, Ojibwe men displayed full regalia which included the wearing of at least one bag. The published photos give an intriguing pictorial history of the Ojibwe in the 1800s and 1900s. In short, the reader wants to learn more about the bag wearers. Some were part of a treaty delegation, some posed for studio photographers, some posed in family portraits.

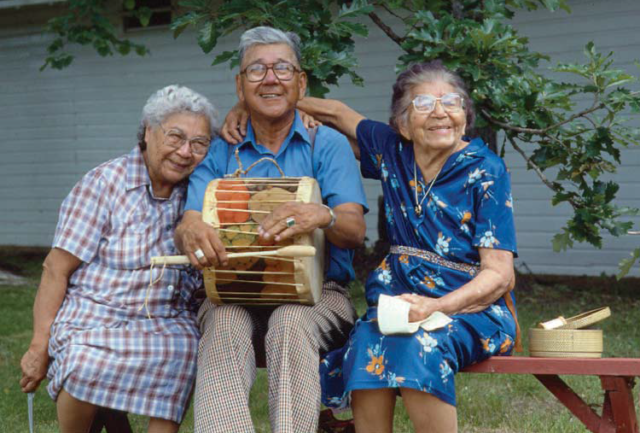

The heart of the book, however, is its second half where artistry comes to life through the stories of Ojibwe women (and a few men) from each Minnesota Ojibwe reservation who created the bags. In mid-book, two of the country’s premier bag creators and respected elders from the Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe, Batiste Sam and Maude Kegg, are pictured with Fred Benjamin. (Fred is misidentified in the photo as Kenny Weyaus.) The photo of these two beloved grandmas depicts pure exuberance and joy, and you’d just like to give each of them a hug.

Maude and Baptiste have passed away, but their amazing talent lives on in the applique bags stored at the Mille Lacs Museum near Onamia. Anderson wrote that the Ojibwe favored floral designs in general, but unique flourishes emerged at each reservation. Distinctive Mille Lacs designs included the cornucopia, the trumpet flower and the seed pod. Anderson wrote: “Maude’s bag was, like most Ojibwe gashkibidaaganag, filled with the fluidity, enthusiasm, and the unique signature of the individual bead artist.”

Maude and Baptiste have passed away, but their amazing talent lives on in the applique bags stored at the Mille Lacs Museum near Onamia. Anderson wrote that the Ojibwe favored floral designs in general, but unique flourishes emerged at each reservation. Distinctive Mille Lacs designs included the cornucopia, the trumpet flower and the seed pod. Anderson wrote: “Maude’s bag was, like most Ojibwe gashkibidaaganag, filled with the fluidity, enthusiasm, and the unique signature of the individual bead artist.”

That kind of conclusion arrives after careful study, but in addition to her research skill, Anderson demonstrates cultural sensitivity and an affection and respect for the women who created these objects of beauty. She pointed out the many decisions a beader made before picking up bead and thread, such as the taste of the man who would wear it. The beader considered the best of what was old and new in bag creation, what beads, thread and fabric were available, and colors and patterns.

Anderson wrote: “And she did all this, with the simplest of resources, while struggling with political oppression that amounted to cultural genocide – forced assimilation, outlawing of traditional religious practices, forced removal of children to boarding schools – and, often, severe poverty.”

Gashkibidaaganag became wildly popular throughout North America especially through the Arts and Crafts period of the 1920s. The women beaders of Minnesota were viewed as the best in the world and the money they earned from bag production was critical to their households.

Again, the book is not for everyone as its detail can be overwhelming at times. But the photographs of gashkibidaa-ganag are gorgeous, and the portion with personal accounts from master beaders is invaluable. If you are a serious student of Ojibwe history, you’ll want to know what is in this book.