By Robert Desjarlait

It wasn’t noticed until April that the Land O’ Lakes iconic image of the Indian Maiden, Mia, was missing. The disappearance of the iconic image was lost amid in the developing outbreak of coronavirus in February. It wasn’t until an article appeared in Minnesota Reformer by Max Nesterak that people took notice.The news of Mia’s demise appeared in national news including the New York Times, New York Post, Star Tribune, Time Magazine, National Review, Indian Country Today among others. And with it came the controversy of the image itself – was it the elimination of a stereotype? Or was it the loss of an image that many Natives felt connected to?

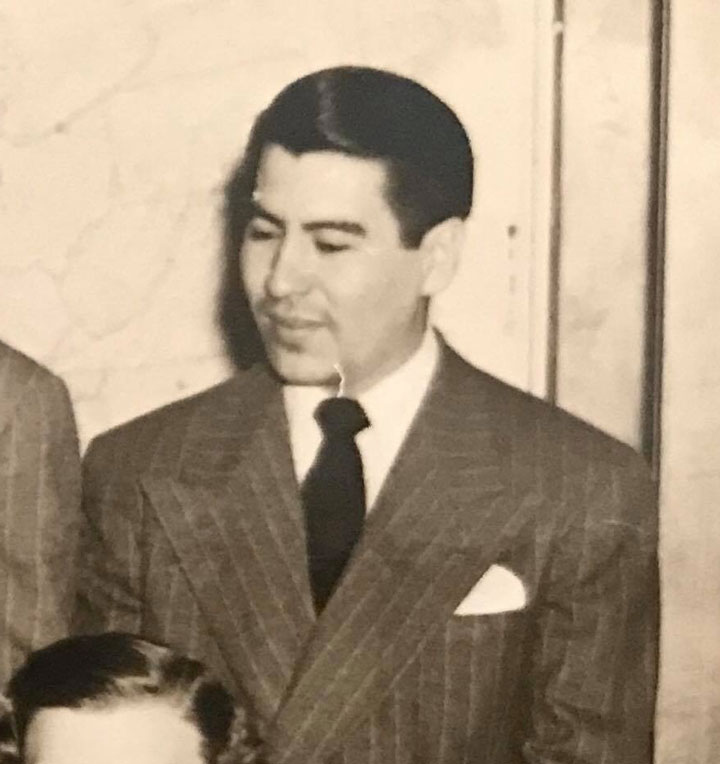

Suzan Harjo, a well-known Native American rights advocate, said that Patrick DesJarlait’s “stereotype of an ‘Indian’ woman is not illustrative or even in the vicinity of his good work.” Harjo’s dismissal of DesJarlait’s skill as a commercial artist overlooks the civil rights barriers he overcame to establish himself in an art world dominated by white advertising executives and artists.

Fresh out of Pipestone Boarding School in Minnesota, he joined the Navy in 1942 and was stationed at the Poston, also called the Colorado River War Location Center, for Japanese internees. He organized a sign and art department as a source of recreation for internees. He was then transferred to San Diego where he worked in the Naval Visual Aids Department producing brochures and promotional films. He worked alongside animation artists from Walt Disney and MGM studios. In the evenings and weekends, he honed his skills as a fine artist.

After he returned home with an honorable discharge, he moved to the Twin Cities. He worked as a staff artist at Reid H. Ray Films which, at that time, was the oldest commercial motion picture company in the U.S.

He worked at several Twin Cities film companies and advertising agencies including Campbell-Mithun Advertising, where he created the Hamm’s Bear, animated Smokey the Bear, and was part of the creation process for the Minnegasco maiden, the Firebird for Standard Gas, and Mia, the Land O’Lakes maiden.

Mia was created in 1928 by Brown & Bigelow illustrator Authur C. Hanson. She was depicted kneeling, in profile, on a wooded lakeshore. In 1939, artist Jess Betlach changed her position to kneeling toward the viewer, holding the butter box, on a farm field with cows and a lake in the distance.

In the 1950s, DesJarlait reimaged Mia. He made her features softer and added Ojibwe floral motifs to her regalia. He eliminated the farm field and put a lake behind her with two forested points of land. Anyone who is familiar with his art would recognize the Narrows at Ponemah where Lower Red Lake and Upper Red Lake meet. It was a motif he used often in his paintings. He placed Mia’s head within the “O” of the brand name, lending an iconographic image to subliminally enhance the beauty of Native womanhood.

But his iconic imagery became lost and forgotten in the era of political correctness. Anti-mascot advocates applauded her disappearance from the label. According to North Dakota Rep. Ruth Buffalo, the Land O’ Lakes maiden went “hand-in-hand with human and sex trafficking of our women and girls….it’s a good thing for the company to remove the image.”

But some saw it differently. Dan McLaughlin (National Review) said, “Color me skeptical that butter labels have any effect on sex trafficking.”

McLaughlin added, “The new packaging no longer has any Native American connection, and erases the work of a Native American illustrator.”

Govinda Budrow is on the faculty of Fond du Lac Tribal and Community College in Cloquet. She says different generations have different relationships with the image.

“I know from my mother’s generation especially, it represented basically the only representation that she had. It was the one thing that smiled back at them to say, hey, other people exist like you and they are out there.”

Budrow said that in disappearing without a trace, and with no one talking about it, Mia has become more like a contemporary Native woman than ever before.

“It just seemed way too ironic when I was thinking about this, about how things happen to indigenous women even now today, where women are being trafficked, they’re being oversexualized, they’re not being heard within spaces, are not being seen within spaces. And then they go missing and there’s nothing being said about them..”

Budrow’s comments reflect the general trend on Facebook in which a majority of respondents, the majority of whom are Native women, posted stories about Mia that supported her existence. Indeed, for many, Mia provided them with a visual, tangible connection to their identities as Native women.

In today’s politically correct world, Mia devolved into a demeaning stereotype. With her absence, the northern landscape, with its lake and forest, is devoid of her beauty. And, like a missing woman, she will be remembered to those to whom she brought comfort and a sense of grace.

Robert DesJarlait is a citizen of the Red Lake Ojibwe Nation. He is an artist and writer. His father is Patrick DesJarlait.