By Lee Egerstrom

Native Americans and Alaskan Natives face obstacles to voting this year, researchers say, and it may be too early to tell if Minnesota will be part of the pack erecting barriers between Native communities and the ballot box.

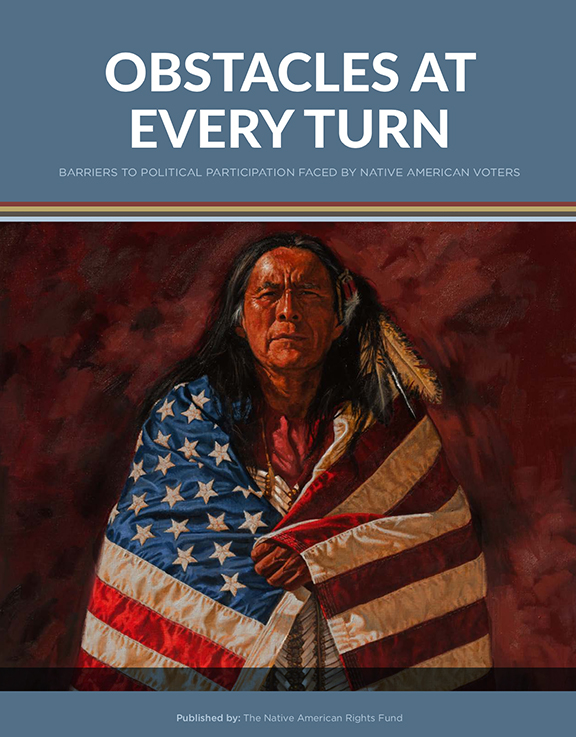

A multi-year study prepared by the Native American Rights Fund (NARF) and the Native American Voting Rights Coalition (NAVRC), based at Boulder, Colo., found widespread barriers to Native voting that range from voter registration requirements, to actual voting, and to getting votes counted.

In Minnesota, lawsuits have attempted to block state efforts to make voting-by-mail easier during the current coronavirus pandemic.

Conflicting state and federal court decisions in June led to a temporary compromise for the state’s Aug. 11 primary election. Barriers to voting by mail and other inconveniences during the COVID-19 will still be in place and potentially may reduce Minnesotans voting in the Nov. 3 general election.

Given voter suppression efforts in other states, however, it is unknown but possible that legal challenges to people’s access to polls in Minnesota will emerge between now and November. Here and everywhere, much is at stake.

“Native American voters have the potential to decide elections,” said Jacqueline De Leon, NARF state attorney and co-author of the report Obstacles at Every Turn. “Forty-four percent of eligible Native Americans are not registered to vote, meaning there are more than 1 million potential Native votes unaccounted for.”

Areas where Native votes can have significant impacts on elections include both Dakotas, Alaska and several Southwest states. They can in neighborhoods and local voting districts of Minnesota as well.

State and county election officials in Minnesota have tried to reduce barriers to voting by encouraging voter registrations and applications to for absentee ballots to vote by mail. Early indications show this is helping.

Risikat Adesaogun, press secretary for Minnesota Secretary of State Steve Simon, said that as of June 25 there were 207,835 Minnesotans who had requested absentee ballots. That compared with 8,964 requests on the same date in 2018 and 7,939 on that date in 2016, the last national election.

This can help keep Minnesotans both healthy and voting this year with the COVID-19 virus a threat to all. At the same time, vote-by-mail isn’t a cure-all for low Native voting turnouts nationwide, said De Leon and NARF staff attorney Natalie Landreth, co-authors of the Native voting report.

Native people do not receive home mail delivery in many parts of the country and cannot vote safely at home, they noted. Language barriers also pose a problem for some voting at home.

Elsewhere, residents of some remote tribal nations need to travel more than 100 miles to either register to vote or to vote at state established polling sites, the authors said. Others have to travel about 100 miles round trip to get state identifications that some state require for voting.

At hearings held during 2017 and 2018, NARF researchers found several common barriers to registering to vote. They included lack of traditional mailing addresses, voter identification requirements, unequal access to online registration (about 90 percent of reservations lack access to broadband Internet), unequal access to in-person voter registration off reservation, unequal access to registration on reservation lands, and unequal funding for voter registration efforts on tribal lands.

The report authors found a lot of barriers in various states that included purges of election roles, lack of pre-election information, unequal access to early voting, lack of Native American election workers and unequal access to convenient polling places.

That such barriers exist shouldn’t be surprising. Wisconsin and Georgia held chaotic primary elections this year, partly – at least – the result of trying to conduct elections with the COVID-19 crisis. While the worst stack up of people wanting to vote wasn’t directed at Native Americans, the lack of adequate voting places in Milwaukee did mostly impact people from marginalized communities.

“In the United States, power is available through participatory democracy. If Native Americans can engage fully in the political system – free from the barriers that currently obstruct them – they can reclaim power and participate in America in a way that is fair and just,” De Leon and Landreth said in releasing their report.

Everything, however, can be politicized, including efforts to get out the vote. Especially in an election year.

The League of Women Voters of Minnesota, along with its groups in other states, went to court earlier this year to get states to waive requirements that absentee voters need a notary or registered voter to witness their voting before mailing ballots.

The common expressed reason was COVID-19. An elderly living alone, for instance, isn’t any more likely to want a visitor come in to witness the voting than wanting to go stand in line to vote at a polling place.

League efforts, joined by other groups, appear to have prevailed in Virginia and Alabama. A compromise was struck in Minnesota, according to Courthouse News Service, after state and federal judges split decisions on similar cases.

Courthouse News Service (CN) is a California-based news service for law firms and has reporters in most major markets across the country. It reported on June 18 that a Ramsey County judge approved a consent decree between the Secretary of State’s office and a group, the Minnesota Alliance for Retired Americans, which sought to eliminate the witness requirement.

Groups in league with the Alliance included the League of Women Voters, the NAACP and American Civil Liberties Union.

A federal judge, meanwhile, blocked that waiver for the November general election. It was sought by Trump’s re-election campaign and local groups of supporters.

Nothing precludes groups from taking more legal runs at how this year’s elections may be held. Such efforts at vote suppression or other reasons would seem likely, in Minnesota and elsewhere, given how the year is unfolding.

To this point, main arguments for opposing vote-by-mail plans and thus deny thousands their right to vote are built around trying to protect against voter fraud.

CBS’ 60 Minutes program on June 28 noted that Oregon, which is exclusively a vote-by-mail state, had well over 2 million votes case in the last election and had 22 cases of voter fraud. Minnesota, meanwhile, had more than 2.9 million votes cast in 2016 and had even fewer cases of suspected voter fraud.

Courthouse News summed up that experience: “Minnesota convicted 11 people for voter fraud in 2016, primarily felons who said they didn’t know they were not allowed to vote.”

Absentee voting in Minnesota began on June 26. Registering, both online and at county offices, for the Aug. 11 primary and Nov. 3 general elections are underway.

• Minnesota voter registration information can be accessed at: https://mnvotes.sos.state.mn.us/VoterRegistration/VoterRegistrationMain.aspx, and at Minnesota county election offices.

• News about the League of Women Voters of Minnesota efforts to increase vote-by-mail registrations can be found at https://www.lwvmn.org/league-news.

• The NARF report, Obstacles at Every Turn: Barriers to Political Participation Faced by Native American Voters, can be seen online at: https://vote.narf.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/obstacles_at_every_turn.pdf?_ga