By Lee Egerstrom

Spring has come to Minnesota and this means weather is far less life-threatening for homeless people living on the streets or holed up in structures not meant for habitation.

This is not a good news-bad news story. There is both improved and worsening news from developments facing the homeless and marginalized communities in Minnesota – rural and urban.

On the bright side, the city of Minneapolis and social service groups announced the Navigation Center providing temporary housing on the edge of the Native American community in south Minneapolis will remain open through May.

Come June, housing for the homeless will be closed at the site for demolition and then the property owners – the Red Lake Nation – will begin construction on a project that includes multiple units of affordable housing. That project is especially aimed at creating housing for Native elders in the metro area.

On April 22, Minneapolis Mayor Jacob Frey declared “Red Lake Nation and Avivo Ending Homelessness Day in Minneapolis,” saluting Red Lake for working with social service nonprofit Avivo in operating the Navigation Center.

The Minneapolis Star Tribune reported 114 formerly homeless people at the center had found permanent housing with help from services, and that tribal and social service groups were still working to find housing for 90 other occupants.

In March, meanwhile, Minneapolis Public Housing Authority (MPHA) opened Minnehaha Townhomes to 16 families, in four buildings near Minnehaha Falls, marking the first new public housing in the city since 2010. Meanwhile, the housing authority is seeking federal Housing and Urban Development (HUD) grants to maintain and update 700 family homes throughout the city.

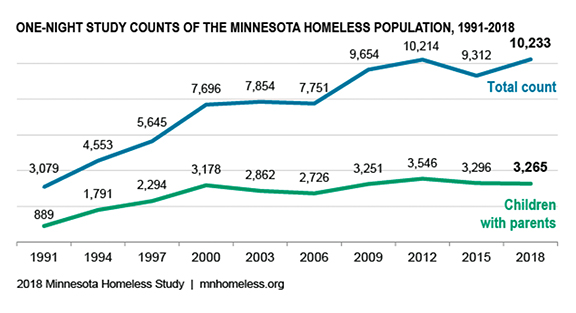

These incremental steps to finding and improving affordable housing come as fresh research shows problems with homelessness are getting worse throughout most of the state, with statewide homelessness up by 10 percent since 2015.

Every three years, the Wilder Research arm of the Amherst H. Wilder Foundation in St. Paul sends researchers out to find, count and interview homeless people on the same survey day. It seeks to quantify the number of people “staying in emergency shelters, domestic violence shelters, and transitional housing programs; as well as people located outside, doubled up, and identified through interviews in outreach locations such as encampments, hot-meal programs, and other drop-in service sites.”

Preliminary findings released in March from the Fall, 2018 survey found the number of people not in a formal shelter increased 62% and the rate of unsheltered children went up 56%. In total, the number of homeless people increased to 10,233 on the survey date, up from 9,312 people on the date in 2015.

Statewide findings sounded exactly like what Native American groups encountered when working with the homeless served at the Navigation Center this past winter.

Citing the Wilder initial findings, the Minnesota Coalition for the Homeless said most people interviewed had spent time staying in a variety of locations throughout the month, including sleeping in encampments, cars, or on public transportation.

The numbers are underestimations, MCH said, because they do not include data from face-to-face interviews conducted in partnership with six of Minnesota’s 11 Native American Tribes.

Further, MCH noted research by the Department of Housing and Urban Development finds 63 percent of people experiencing homelessness identify themselves as People of Color or Indigenous Peoples.

“Sixty-three of Minnesota’s 87 counties do not have a fixed site shelter. If we maintain the status quo, this dangerous trend line will continue. Encampments will become more frequent and the number of Minnesotans sleeping outside in life threatening temperatures will continue to climb,” said Senta Leff, executive director at Minnesota Coalition for the Homeless, in a statement.

Tad Vezner’s report in the St. Paul Pioneer Press showed this isn’t just a south Minneapolis, or Twin Cities urban problem. He reported that metro homelessness was up 9 percent from the 2015 Wilder survey while rural homelessness increased by 13 percent.

An alarming statistic gleaned by Vezner is especially important for the American Indian communities, rural and urban, and reflects the urgency of what Red Lake Nation is planning for its Minneapolis property. Older adults from age 55 and up had the biggest jump in homelessness from 2015, up 25 percent.

The St. Cloud Times account of the Wilder study noted Central Minnesota homelessness increased 20 percent since 2015. A majority of Central Minnesota’s homeless involved families with children.

John Lundy, writing in the Duluth News Tribune, said Wilder researchers found a 23 percent increase in St. Louis County homelessness in the last three years. Lundy’s report also got to the center of some of the homeless problems.

He reported: “We did not have rampant opioid and drug use (in 2015),” said (Lee) Stuart, the executive director of CHUM, a faith-based nonprofit that shelters and serves homeless people in Duluth. “Our analysis of this is (that) between 2015 and 2018 the biggest (thing) on the streets is drugs. And that’s what is driving this.”

That observation from Duluth echoes what Native American leaders and service providers have blamed as a major factor in metro area homelessness, especially in and around the Franklin Avenue American Indian Cultural Corridor.

It also signals the problems community leaders, government agencies and non-governmental service providers face going forward in urban settings. An April 16 announcement from the Southwest Minnesota Housing Partnership noted that HUD agencies had declared the 18 counties in the Southwest Minnesota Continuum of Care region had ended what HUD defines as “chronic homelessness.”

Kristie Blankenship, interim chief operating officer for the Southwest Partnership group, cautioned in the announcement that Southwest Minnesota still has problems of homelessness to address that fall under different HUD and state definitions.

“Chronic” is a narrower definition of people with repetitive homelessness episodes for either the past year or the past three years, she said in an interview. “We’ve made progress but we still have work to do,” she added.

HUD has revised some definitions of homelessness. In short, the definitions include people who are living in a place not meant for human habitation, in emergency shelter, in transitional housing, or are exiting an institution where they temporarily resided; people who are losing their primary nighttime residence, which may include a motel or hotel or a doubled up situation, within 14 days and lack resources or support networks to remain in housing; families with children or unaccompanied youth who are unstably housed and likely to continue in that state; and, people who are fleeing or attempting to flee domestic violence, have no other residence, and lack the resources or support networks to obtain other permanent housing.

A Fact Sheet on the Wilder Research homelessness study can be found at http://mnhomeless.org/minnesota-homeless-study/reports-and-fact-sheets/2018/2018-homeless-counts-fact-sheet-3-19.pdf.

Other sources in this article are found at:

• www.mnhomelesscoalition.org

• www.wilder.org

• www.duluthnewstribune.com/news/government-and-politics/4587623-st-louis-county-homelessness-23-percent

• www.sctimes.com/story/news/local/2019/03/22/central-minnesota-homeless-population-grows/3247623002

• www.startribune.com/as-navigation-center-prepares-to-close-114-homeless-people-find

housing/508977882/.