By Lee Egerstrom

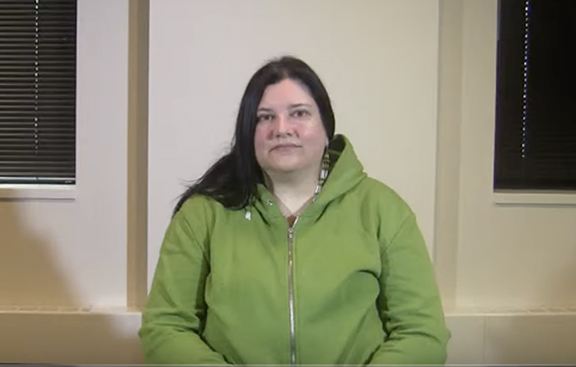

Iyekiyapiwin Darlene St. Clair spent the last week of June directing a workshop for educators at Grand Portage in Northern Minnesota. It marked the second time educators have gathered to study the history and culture of the Grand Portage Anishinaabe in her workshops.

St. Clair is an educator who teaches other educators and future generations of teachers at St. Cloud State University. There is a lesson all educators should learn, she said, “If you are teaching in this area (Minnesota), you are teaching on indigenous land.”

She has taken workshops to all 11 reservations in the state. While some attendees work at museums or have other positions where Native knowledge is crucial, most are K-12 or higher education teachers who often return for more workshops to broaden their knowledge of Dakota and Ojibwe history and culture.

What St. Clair has learned over the years is that conscientious educators really do want to learn more and teach more about Minnesota’s indigenous people and, as a result, more about Minnesota’s history for all interconnected people.

St. Clair is a highly-charged educator and stimulator of Native Minnesota education who is doing precisely what the Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux Community and education consultant Odia Wood-Krueger are encouraging. See companion article about SMSC’s Understand Native Minnesota project and Wood-Krueger’s report, “Restoring Our Place: An analysis of Native American resources used in Minnesota’s classrooms.”

St. Clair could easily be called a whirlwind. That is shown in the Spring-Summer 2022 edition of St. Cloud State Magazine that salutes SCSU faculty members for their work in assisting teacher-scholars on a number of subjects. An associate professor of American Indian Studies and director of the Multicultural Resources Center at St. Cloud State, St. Clair runs the summer workshops for educators who want to learn more to improve their classes and to help their students. The workshops can also be taken as a credit course.

From her campus base at St. Cloud State, she also works with students on specific projects. These include research and learning about Dakota and Ojibwe history in Central Minnesota, and, for the past 10 years, with projects in the Twin Cities identifying and explaining historic and sacred places for Dakota people.

The SCSU magazine article notes that she addresses inherent racism in educational experiences with both her work as a classroom teacher and with the Multicultural Resources Center. The latter supports students, SCSU faculty and the larger St. Cloud-Central Minnesota community.

One course she teaches is called Native Nations of Minnesota. It has students explore how the university’s campus, St. Cloud community itself, and all of Central Minnesota are indigenous places, she said.

“St. Cloud State sits on the banks of the Mississippi River that has endless ties to the Dakota and Ojibwe,” she said an interview with The Circle. “The Beaver Islands are part of that history.”

Those islands were named by Zebulon Pike in 1805 on his exploration of the Mississippi River, stretch for about five miles from the SCSU campus to below the city. Some of them are SCSU property.

This history becomes personal for St. Clair, a member of the Lower Sioux Indian Community who actually grew up in Minneapolis. On that same exploration of the river, Pike negotiated a treaty with Dakota leaders for land at the confluence of the Minnesota and Mississippi rivers.

It was to allow for a fort (Fort St. Anthony) to be constructed to protect the waterways if needed in a possible war with England that became the War of 1812. That fort later become Fort Snelling – a place steeped in history for Dakota people.

Central Minnesota has deep Native roots that come as a surprise to some students. Beyond the role the river has played with Dakota and Ojibwe people, there are other nearby places clearly linked with Minnesota’s Native populations. “Our nearby institutions, or campuses, operated as Indian boarding schools,” she said.

Indeed, Saint John’s Abbey at St. John’s University and the College of Saint Benedict, at nearby Collegeville and St. Joseph, were part of the federal government’s forced assimilation program by separating families and sending children to boarding schools. Nuns from the Order of St. Benedict also operated two boarding schools on the White Earth and Red Lake reservations.

“Not all our history was about or ended with the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862,” she said.

Clair teaches classes on Native arts and cultural expressions. She is adding a side group (a “cohort” in education speak) of Native American students and art education students who want more knowledge of Native arts and their ties to history. This cohort is with a class she teaches on Native arts and cultural expressions.

“Some are Native students. Some are art or art education majors. A non-Native student might say, ‘I went to a powwow as a child and I want to learn more.’

“We (Native Americans) are still here. We still care about the land and our traditions. There’s a big intellectual shift underway. A lot of students (in the past) believed Native people were a long time ago.

“We can dismiss stereotypes,” she said.

St. Clair also teaches using Native American literature, a point of importance emphasized in the Wood-Krueger education report. “We think about poetry. This is a fun class to teach. The students want to read more literature from diverse authors.”

For those culturally broadening reasons, she finds her classes also appeal to international students. Some of these students have experiences with what colonization did to their own indigenous cultures, or what their countries did to indigenous people. “It is historical what colonialism did all over the world,” she said. “It’s amazing how similar our stories are.”

St. Clair suspects many Minnesotans who don’t know about the impact of colonialism on Native people are products of “intentional forgetting.” “It is the erasure of Native people from public consciousness,” she said.

Getting to know the professor is a cultural lesson in itself. Her Dakota name, Iyeliyapiwin, means “recognized woman” and was given to her as a young adult at a Lower Sioux community naming ceremony.

In Dakota, she said, it has a different meaning than what it implies in English. “It means I recognize things as they are. This is a chair. This is a cup. It is something I think about a lot.”

The English translation conveys the image that she is a woman, an educator, who stands out and is recognized, as she was in the St. Cloud State magazine.

Both definitions seem especially accurate.