Review by Deborah Locke

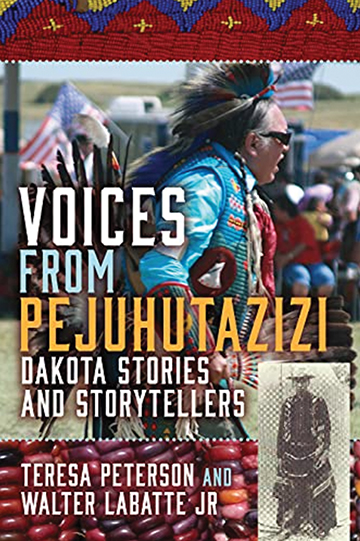

“Voices from Pejuhutazizi: Dakota Stories and Storytellers” features five generations of stories from a family living at Minnesota’s Upper Sioux Community near Granite Falls. The stories tell the impact on individual family members of big historical events like war and migration, and they give insight into the less dramatic details of a life, like making moccasins or corn soup.

For those well-versed students of Dakota and American Indian history, the book will make a nice addition to your bookshelf. It gives unusual details of accounts not often discussed, like the fierce and bloody battles between sworn enemies the Dakota, Crow and Ojibwe.

For those only starting to learn American Indian history in Minnesota, the book is a good introduction to the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862 and federal policies like relocation, as well as examples of day-to-day Dakota life. What I liked best were the nuggets of wisdom, humor and humanity from storytellers/authors Teresa Peterson and Walter “Super” LaBatte, Jr.

Peterson (Sisseton-Wahpeton Dakota) is an educator and tribal planner from Upper Sioux Community, and her uncle, Super LaBatte Jr., (Sisseton-Wahpeton Dakota) is an artist, hide tanner, retired carpenter and maker of drums, beads and moccasins. Also, he’s a graduate of St. Paul’s Macalester College with a degree in German, and like his niece, is an Upper Sioux Community member.

The book chronicles stories told and heard over generations of time in their family, including the 1910s when Fred Pearsall took notes on stories from Dakota elders and retold the stories in 1950s letters to his daughters and to his grandson, Super LaBatte.

Many of the contemporary stories originate with Super, the son of a Presbyterian church elder, who explains the important role the Presbyterian church played in his life. The book takes on a memoir-like flavor at times as Super relays his battle with alcohol addiction and how he overcame it, or the magical moments of entering a powwow arena in dance regalia for the Grand Entry.

Super, who speaks fluent German, wrote that it wasn’t unusual to see Germans at the summer powwows. He could identify them by their German accents while speaking English. He wrote that he would approach the German powwow spectators in his dance regalia and in German, asked if they were from Germany.

“At first there is this stunned second or two of silence, and I can see that their eyes and their ears are in conflict. There is no recognition of what is happening. So, I continue in German, saying, ‘Oh, it only appears that I am an Indian, but I am really German.’ Another stunned silence of disbelief.’”

After another pause, the German visitors finally realized the truth, that Super was an Indian who spoke German. He wrote that the next time this happens at a powwow, he will turn to the visitors from Europe and ask if he can take their picture, a reversal of the norm.

Early in the book seven core Dakota values are listed, that remind the people “how to live and be with each other.” The values are compassion, respect, wisdom, courage, patience, generosity, and humility. Examples of each are cited, as well as others, like the value of working hard. Super’s wisdom shines when he points out that not all American Indian traditional spiritual practices were prohibited by U.S. government officials. Certainly that didn’t happen at the Upper Sioux Agency, where stories of the sweat lodge were common.

Super wrote that his people may call themselves Dakota, they may call themselves American Indians, but the people do not have the same belief systems, don’t follow the same protocols, don’t have identical cultural and spiritual ways. He wrote:

“So it takes a small mind to criticize others for not following your ways. After the diaspora, (the period when the Dakota were forced out of Minnesota and scattered), we were all raised in unique geographic areas, different eras; and were taught different ways from our parents. The answer is acceptance, in order to maintain peace and serenity.”

It’s the excerpts like the above, among stories about bears, skunks, drums, hymns and skirmishes that makes this book stand out. The approach is gentle, and universal, with reminders that we all have stories to remember and share, and that when we know our own stories, “no matter where you go, you belong. Stories have roots to the past that lead all the way back to the source of all things…stories shape future realities.”