By Lee Egerstrom

Native American families have more difficulty accessing home mortgages for property on Indian reservation and pay higher interest rates for their loans than the general U.S. population living off reservation trust lands.

While that has generally been assumed for decades, prompting federal loan programs in the past, a study by economic researchers at the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis’ Center for Indian Country Development brings current data into view.

The Fed Center’s (CICD) study shows the higher cost home loans are especially used for purchasing manufactured homes that are common within U.S. reservation communities.

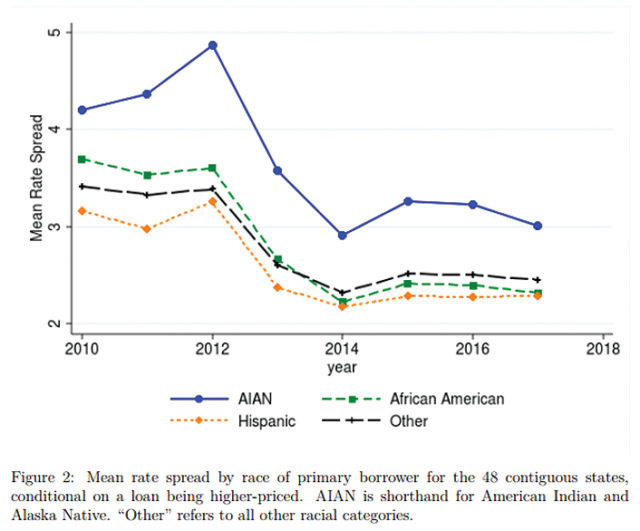

The study, prepared by research economist Donna Feir and research assistant Laura Catteneo, showed that home buyers on reservations pay about two percentage point higher interest rates for mortgages on reservation lands compared to non-Native buyers outside the reservations.

This means a Native buyer or family on a reservation with a $140,000 mortgage written in 2016 will pay about $107,000 more for their home over 30 years than similar buyers off reservation land. While that is huge, it applies to Native buyers who secure mortgages; gaining access to mortgage money is also more difficult for the Native communities.

Feir and Catteneo’s study showed that approximately 30 percent of American Indian and Alaskan Native (AIAN) loans on reservations carried interest rates higher than loans made to non-Native Americans. Only 10 percent of loans to non-Natives for properties near reservations were at higher costs, resulting in Natives paying higher rates at three times the rates for non-Native borrowers.

Manufactured homes account for 25 percent to 35 percent of the higher cost of financing on reservation lands.

In releasing the study on Oct. 2, Feir said more study of manufactured home financing “might be necessary if home loans are going to be made equally affordable for AIAN borrowers.”

Like much economic research, the CICD study entitled The Higher Price of Mortgage Financing for Native Americans quantifies economic disparities affecting Native home ownership but leaves finding solutions to policy makers and community leaders.

That process may have gotten a start on Oct. 16 when the U.S. Senate Committee on Indian Affairs held a hearing in Washington on homeownership lending in Indian Country.

Patrice Kunesh, the CICD director and a vice president of the Minneapolis Fed, referenced the CICD study and told senators that home ownership has long been a path to creating social and economic health and wealth in America. “But Native Americans have largely been denied this opportunity, especially those living on reservation trust lands,” she said in prepared testimony.

In suggestions to the committee members, Kunesh said that while tribes have sovereignty over their lands, they do not control complex federal processes to put the lands into productive use. She cited Bureau of Indian Affairs processes that impede housing and affordable lending practices.

“For example,” she said, “the (Housing and Urban Development) Section 184 Home Loan Guarantee Program is a very popular and much-needed program. But in recent years, 93 percent of its loans have bypassed reservations mostly because of administrative hurdles.”

Impediments to programs deprive Native people, including her own family from the Standing Rock reservation in South Dakota, from building personal assets, Kunesh said. What’s more, these impediments to family asset building discourages investments to create prosperity throughout the Native communities.

Kunesh encouraged the lawmakers to consider ways to expand access to capital and credit in Indian Country.

“As conventional lenders have retreated from Indian Country, Native Community Development Financial Institutions, or Native CDFIs, have become critical sources of capital for home loans. They intimately know the lending needs and capacity of their constituents,” she said.

Closely working with and financially supporting CDFIs would help deliver federal programs such as the HUD 184 loan guarantees, the U.S. Department of Agriculture Rural Development 502 home loans and the Veterans Administration’s Native American Direct Loan program, she added.

Kunesh also told the senators that public housing and loan programs should use “innovative” loan products and delivery systems. One example she noted is USDA expanding access to public capital by producing Native CDFIs in South Dakota with re-lending authority for Section 502 home loans on trust land.

“That could mean access to millions of dollars of housing investments in Indian Country,” she said.

The Senate committee is chaired by Sen. John Hoeven, a banker by profession and former Republican governor of North Dakota.

Among others testifying before the committee, Fort Belknap Indian Community Councilman Nathanial Mount told of several efforts underway by his remote north-central Montana community that seem to back up Kunesh recommendations.

The joint Gros Ventre and Assiniboine Tribe, or the self-identified Aaniih and Nakoda people, Fort Belknap has acquired a custom home (manufactured) building business that is preparing a subdivision project at Billings. This will help Fort Belknap lower costs and create materials efficiencies for building on-reservation housing as well, he said.

In addition, Fort Belknap is creating its own mortgage lending operation, has brought in a conventional mortgage specialist to set it up, and is preparing to offer affordable tribal mortgage products to be sold into the Federal Housing Finance Agency’s Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae secondary mortgage markets.

“In short, we are actively working all aspects of planning for housing development, save (for) the biggest one – our residential leasing authority – until we have DOI (Department of Interior) approval,” Mount said.

What’s afoot at Fort Belknap will either prove to be innovative responses to the housing challenges on Native reservations, like Kunesh suggested, or fall to impediments to reservation progress that she also cited.

The Minneapolis Fed serves the Ninth Federal Reserve District that includes parts of Michigan and Wisconsin and the states of Minnesota, North and South Dakota, and Montana. Kunesh noted in her testimony that there are 45 Native American tribal nations within that territory.

The Center for Indian Country Development was created by the Minneapolis Fed but serves banks and programs for all 12 Federal Reserve System districts. It focuses on economic and development issues for American Indian and Alaskan and Hawaiian indigenous people.

“The Higher Price of Mortgage Financing for Native Americans” can be found at: https://ideas.repec.org/p/fip/fedmci/2019_004.html