By Dan Gunderson/MPR

Anton Treuer calls himself an Ojibwe language warrior. He’s been working to preserve and share the language for two decades. He spends a lot of time learning from elders, and over the past year COVID-19 has claimed many.

“It’s been hard. We’ve simply had a lot of deaths,” said Treuer, whose work takes him to tribal communities in Minnesota, North Dakota, Wisconsin and Ontario.

“And throughout those communities, the COVID deaths have been profound,” he said. “We identified 25 fluent [Ojibwe] speakers in Mille Lacs, and about half a dozen of them died this year, most from COVID.”

Fifteen years ago, 145 members of the Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe were fluent in the language. As those numbers have dwindled, the impact of each loss compounds.

That’s why the numbers of elders lost to the pandemic at Mille Lacs has been devastating to Baabiitaw Boyd.

“I don’t think any of us were ready for what COVID had for us,” she said. “We’re stunned. Our hearts are heavy.”

Boyd has worked for about 15 years to preserve language and culture among the people of the Mille Lacs Band, where she is the tribal government’s commissioner of administration.

Some of the elders lost to COVID-19 carried generations of knowledge about language and culture. Boyd believes transferring that knowledge to future generations is critical to the very survival of the Ojibwe people.

“I think there’s a tendency among people who are not from a marginalized language community to think that the main value of a language is just that it’s like another pretty bird singing in the forest,” said Treuer.

And that can make it easy to minimize the loss of language and culture, he said. But losing a single fluent speaker of a rare language can threaten the social and cultural fabric of a community, said Treuer – and it leaves the world a poorer place.

“Embedded in Indigenous languages are unique worldviews that can and should pollinate the garden we’re all trying to harvest from, and help lead us in new and different directions,” he said. “That’s a gift we have for the world.”

Boyd says she knew, as the pandemic loomed, that COVID-19 was a significant threat because of health disparities that already existed among Native people – disparities that put many at higher risk for serious COVID-19 illness.

While privacy concerns limit the information available about COVID-19 deaths in tribal communities, Minnesota Department of Health data shows that more than 5,000 American Indians have tested positive for COVID-19 in Minnesota – and more than 90 people have died from complications of the disease.

At times the losses, Boyd said, have felt overwhelming.

“We’re resilient, we’re staying strong, we have our cultural teachings that we rely on to process that grief. And we’re showing up for one another, to the best of our ability. But the effect is that we’re all very, very sad,” said Boyd. “And at the same time, we feel a tremendous amount of pressure to collect information so that we have the intergenerational transmission of knowledge.”

The knowledge carried by elders isn’t just about learning a language. The stories they carry are important to understanding culture and spirituality.

“Every family has a story about their family, their place in the band, and a lot of stories have nuances to the culture, that when they’re gone, they’re gone,” said Steve Premo, an artist from Mille Lacs who has illustrated many Ojibwe language books. “You can’t get them back again, the stories that they take with them. It’s so hard to think about all the knowledge that they take with them.”

The threat of COVID-19 to elders served as a turning point for Boyd, who has been studying under those elders for 15 years. To protect them, and keep them isolated, she and two other younger members of the Mille Lacs Band took on new roles during the pandemic, leading funerals and other spiritual ceremonies.

“It’s terrifying to be responsible for somebody’s spiritual well-being, when you’re not really even sure if you’re well enough, or practiced enough,” said Boyd. She expected to some day to take on that role, but not while her teachers were still alive.

“I don’t even have the right word for the sadness, and the overwhelming feelings that came with that,” she recalled.

In some communities, such ceremonies have always been led by the remaining first language speakers. During that pandemic, that was no longer possible.

“We’ve had an unbelievable number of funerals this year,” said Treuer, who has conducted funerals in tribal communities across the region. “And we’ve also seen a new generation of young, emerging language- and culture-keepers step up. And I think COVID provided an inflection point that catalyzed their growth and development.”

Treuer himself has had to adjust his language research to protect elders. And he’s lost research subjects who he calls dear friends.

“It’s been rearranging everybody’s world in a lot of different ways. But yes, I’ve felt this as a personal loss,” he said. “And I’ve also felt this as a community stress.”

Treuer thinks often about his longtime mentor and friend, Red Lake spiritual leader Eugene Stillday, who died of COVID-19 last year at 89, and called him by his Native name, Waagosh.

“I’m sure, he would be saying, ‘Well, Waagosh, get up and get out there and get something done and keep going, you know, I’m counting on you,’” said Treuer.

Boyd, too, thinks about what those elders who are gone would want – and she knows they would expect resilience in the face of tragedy.

“It’s a loss, and we suffer that loss together when we lose a fluent speaker,” she said. “But we focus on what we have, and we try to stay in a place of gratitude about that.”

Boyd and Treuer say while many tribes have made great progress in preserving cultural knowledge and language, much work remains.

“Its best to classify the Ojibwe revitalization efforts as emerging,” said Treuer. “As much progress as we’ve made, we’re not full circle yet, with a thriving and growing base of speakers that will continue to scale up and grow without major interventions.”

There are expanding efforts to create language immersion schools in many tribal communities, but those initiatives are limited by a shortage of trained teachers.

“Our goal is to move revitalization to a place where people will effortlessly be able to speak and understand Ojibwe and read it, and live from an authentic place with Ojibwe,” said Boyd.

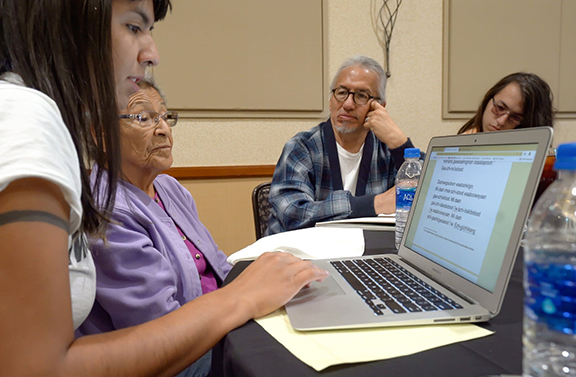

In addition to the expanded role for this younger generation of leaders, the pandemic brought changes that might have a long-term impact on language and culture preservation. For Treuer, it’s helped incorporate technology in new and beneficial ways.

“Some of the elders who are a little skeptical about, you know, ‘I don’t know, if we should be using a computer to do a storytelling thing,’ they were like, ‘Hook it up, let’s go, I want to talk to some people,’” he recalled.

“And I think that helped us forge and strengthen community at a time when we were being physically separated from one another.”

Treuer has finished two language books during the pandemic, and remote work continued among many people working to create an Ojibwe Rosetta Stone language course. He said he thinks technology can help break down barriers of space and time for teaching Native language and culture to a new generation.

“We can be ancient and modern, all at the same time,” he said. “And I feel like, you know, the stresses and tests we’ve had with COVID have catalyzed our efforts.”