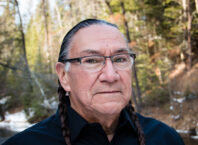

By Arne Vainio, MD

Can you tell the story of how you became a doctor? It seemed like a simple enough question, “Dr. Vainio, can you tell the story of how you became a doctor?” I thought that would be a relatively straightforward story, but it isn’t. Like anything else, this is bits and pieces and twists and turns and dead ends and parts of it aren’t even my story. The hope was this would be an inspirational story to be able to show kids and anyone else hoping to go down this path.

When I was a boy, most other boys wanted to be firemen or astronauts. Truth be told, until I was four years old my parents owned a bar called the Good Luck Tavern. The pulp truck drivers would stop in and drink beer and one of them let me stand on his lap and drive a big truck loaded with logs across the bumpy dirt parking lot and I was hooked.

I wanted to be a truck driver.

I wasn’t an exceptional student in grade school or in high school and I don’t know that there were any great expectations of me from any of my teachers. I worked on a dairy farm in the 11th and 12th grade in high school and thought maybe that’s where my fate lay. Then I played pool one night with a man with white hair and he hired me on the spot to work construction as there was really no one else available. He showed me the basic levers and principles behind running a backhoe and a bulldozer and he left me working while he went to argue with attorneys over some contract issues.

That ended up as a job that would take me to multiple places in Minnesota, Wisconsin, Colorado, Montana and North Dakota. I learned to read construction blueprints and to oversee subcontractors and turn in weekly progress reports to the Army Corps of Engineers. Eventually I decided I needed to return to Minnesota and I took a job cutting the limbs from jack pine trees with a chain saw. That turned into running a skidder dragging trees out of the woods so they could be loaded onto trucks.

That was a great few years and then I decided I wanted to learn to paint cars. I worked in a body shop for a year or so and I ran a sandblaster taking the rust and paint off logging trucks and trailers and I started to learn how to paint. I loved every minute of every single one of those jobs.

During that time I was in and out of college and didn’t do very well at all. After my first two quarters, my Grade Point Average was 0.00. I didn’t pass a single course and the University suspended me.

Somewhere in there Edwin Peterson died. I don’t remember exactly when in between all those jobs, but his death hit me hard. He was the uncle of my cousins and was maybe 70 or so when he died. He was constantly making home brew in an old crock in his closet and we made fish traps together and his house was always a safe place to take a deer we might have shined at night or to take a trap full of fish to clean out of season. He saw the humor in any situation and his house was a good place to be.

He was feeding his pigs one day and there were people with him when he suddenly fell to the ground. He didn’t have a phone, so someone had to drive a quarter mile to call the ambulance. This was a volunteer service from 25 miles away and the ambulance crew had to be called in. It was almost an hour before they got there and they were far too late to save him.

I never wanted to be one of those people standing helplessly waiting for the ambulance and I took a 110-hour Emergency Medical Technician course. This was the first taste of medicine I’d ever had and I liked it, but when the course was over, it was simply over and I went back to work.

I was machine sanding a car one day and I could feel the impact as the pickup hit a logging truck head on at the intersection just outside the body shop. The logging truck was building speed to make a long hill when the crash happened and the pickup had the engine pushed under the seat and the hood was pushed almost to the windshield. There was a woman inside and she was covered in blood and lying on her side behind the steering wheel and she couldn’t hold her head up.

Broken glass was everywhere and it was crunching under my knees as I made my way into the cab of the truck. She was moaning and crying and her voice bubbled through the blood in her mouth as she kept asking me what happened. I kept talking to her softly and gently brushing the blood and hair out of her eyes as the sounds of traffic and the hissing of the tires on the logging truck slowly gave way to the sirens of the ambulance and a squad car and I continued to hold her head still.

I held her neck steady as the ambulance crew slid the backboard over the broken glass on the seat and they reached in through the missing windows to lift her onto the hard plastic backboard. They were slipping the cervical collar around her neck and I could finally slowly release her head and neck. The Velcro straps were going over her arms and legs to secure her onto the board so they could put her into the ambulance. She could only see a little bit of the sheer magnitude of what had happened to her and the destruction the logging truck left behind. She looked back at me and she smiled and she whispered, “Thank you”.

Something changed inside me as I was kneeling in the blood and the broken glass inside that pickup truck on a hot midsummer day with the cicadas buzzing incessantly and a woman I’d never met looking into my eyes and knowing I was her best bet. At that moment nothing mattered except me and her.

If you save a life just one time, that single event defines you as a person. I went on to be a professional firefighter and then a paramedic for the City of Virginia, Minnesota and my experience in the cab of that pickup truck is what led me there. I loved being on the Fire Department and those were my brothers in every sense of the word. Much of what I do now as a doctor was learned in the back of an ambulance or in a ditch kneeling in blood and broken glass and we saved lives again and again and again.

The story of how I became a doctor has several beginnings and maybe the middle part has a few different versions depending on what part of being a doctor I’m thinking about.

I don’t know how it ends, but I hope it’s a long, long time from now. I imagine I’ll close my eyes as the cicadas buzz and the sun will be beating down and I’ll see the eyes of a woman I’ve met once before go from fear to calm as I tell her a story to pass the time while we wait.

Arne Vainio, M.D. is an enrolled member of the Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe and is a family practice physician on the Fond du Lac reservation in Cloquet, Minnesota. He can be contacted at a-vainio@hotmail.com.