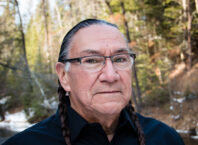

By Arne Vainio, MD.

Warren was dying and there was no changing course. His lung cancer had spread since he was in the hospital last time and his liver failure was worse. He tried to stay sober when he got out of the hospital and that lasted less than a month. He lived by himself in a small apartment and just barely made the rent payments. When he came in to the hospital this time, he clearly hadn’t changed clothes or taken a bath in weeks and he had cigarette burns in his dirty white shirt. He had thick yellow skin between his right index and middle fingers from decades of holding hand rolled ciga- rettes.

When he was sent out from the hospital last time, he was supposed to see a specialist to have a lung biopsy, but he didn’t show up for the appointment and he never answered his phone. He wouldn’t make eye contact with me when I was admitting him to the hospital and he knew me well from his last stay.

This was twenty-two years ago and I was still a relatively new physician in Seattle. It took me a long time to get the history I needed and to do my exam. He had bruises on his back and his legs and some of them were recent and some were much older. He took a while deciding if he wanted to tell me about them.

“I fall sometimes. Drunks do that, you know.”

“What makes you fall?” I asked.

“Mostly alcohol, sometimes coughing fits. Sometimes both.” He answered.

“What did they tell you in the Emergency Room?” I asked.

“They said my cancer is worse, but I knew that. You and I both know I could never tolerate chemotherapy and I’ve had surgeons tell me they won’t operate on me because my liver is too bad.”

“How do you think your liver is doing now?” I asked.

“They said it’s worse in the Emergency Room. I knew that, too. The fluid in my belly is building up again and I’ve never been this yellow.”

I knew the answer to both questions before I asked him and I just wanted to know what his understanding was. He clearly had no illusions about his prognosis.

When he was in the hospital last time, no one came to visit him and he didn’t want to talk about it and said he just wanted to be left alone. He didn’t let the home health nurse come into his apartment when she came to check on him.

This time he was in the hospital for almost two weeks and I saw him every day. He was in alcohol withdrawal for almost a week and he was miserable and hallucinating. He was finally clearing when I went in to see him. He was still short of breath and he was still jaundiced. His liver tests were getting worse and his kidneys were starting to fail.

I listened to his lungs and I could hear the coarse sounds where his cancer was. He was working hard to breathe and his sentences were short. His heart was beating hard because of the extra work it had to do with his anemia. He had already been transfused twice and he was slowly weeping blood from inside his stomach. His liver couldn’t make the clotting factors he needed and it was hard to get him to stop bleeding.

His belly was still distended, even though the Radiologist had drained off over 8 liters of fluid. Normally there is about a tenth of a liter of fluid in the abdominal cavity to allow our internal organs to slide against each other.

“You’re still pretty sick, Warren.” I told him.

“I know.” He said. “I knew one of these times would be the last. Is this it, Dr. Vainio?”

“I don’t know, Warren. It doesn’t look good.”

He closed his eyes for a few seconds, then he opened them and looked out the window. It was a perfect summer day in Seattle and the few clouds slowly drifting were big and billowing against a deep blue sky and looked like they could be on a post card. He kept looking out the window.

“Can I ask you something, Warren?” I asked.

He didn’t look at me. “Sure.” He said quietly.

“Who’s Danny?” I asked.

Tears welled up in his eyes and he continued to look out the window. “Where did you get that name?” He asked.

“From you.” I told him. “When you were hallucinating you kept telling him you were sorry.” “It’s too late to be sorry, Dr. Vainio. I’ve poisoned everything around me. I’ve done that since I ran away from home when I was fifteen. My father was a drunk and I couldn’t get out of that house fast enough. I swore I would never be like him and I turned out to be a spitting image of him in every way.”

“Where is Danny now?” I asked.

“I don’t know. My wife left with him when he was four years old and she never looked back. I signed some divorce papers years ago when I was drunk and I haven’t heard from them since. She had family out on the east coast and they would never answer any questions.” “Do you think about him?” I asked.

“I do. I deserve to die alone, Dr. Vainio. I was never any kind of father and I stopped at the bar on my way home every time I got paid. I never took him to a park or swimming or to a fair. I wasn’t any better husband than I was a father. I told my wife she was the cause of my drinking. Maybe I was wrong,” he smiled grimly, “they’ve been gone for over thirty years.”

“You’ve been alone all these years?” I asked.

“Mostly. I had a couple of dogs I really liked. One got old and died and one was taken away by the Sheriff when I went on a two week drunk and left him in my apartment.”

He was getting more short of breath and he was having a hard time talking.

“Is this hard for you to talk about, Warren?” I asked. “Would you rather talk about this at another time?”

“You started this, Dr. Vainio. I’ve never talked to anyone about this and I don’t have anything to hide anymore. I know my cancer is terminal and my liver is getting worse. I know I won’t make it home this time and even if I did, it’s a miserable existence.”

He was breathing harder and it took him quite a while to catch his breath. He finally started talking again.

“I poisoned everything I touched, Dr. Vainio. I poisoned my marriage, I poisoned my chance at being a father and I poisoned myself. I would never expect Danny and his mother to come back to me and I imagine they found themselves a real good life someplace far away. Danny needed a chance to grow up in a house without drunks. He would be about 35 years old and I’ve sometimes stayed sober on his birthday. I wish I could have given him the life he deserved.”

He went downhill rapidly after that and that was the last real conversation I had with him. He was too sick to send anywhere and he died within a week. As far as I know, he didn’t talk to anyone else.

I haven’t thought of him in all these years. Not long ago I saw a young man step up as his father’s cancer spread. He was fearful and uncertain, but his love for his father prevailed. He was at every doctor visit and he stayed by the bedside and held his father’s hand as he was dying. A relationship like that is a privilege and a responsibility and it’s the way things should be.

Not everyone gets that chance.

Are you out there, Danny? I knew your father.

He wanted me to tell you he was sorry.

Arne Vainio, M.D. is an enrolled member of the Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe and is a fam- ily practice physician on the Fond du Lac reservation in Cloquet, Minnesota. He can be contacted at a-vainio@hotmail.com