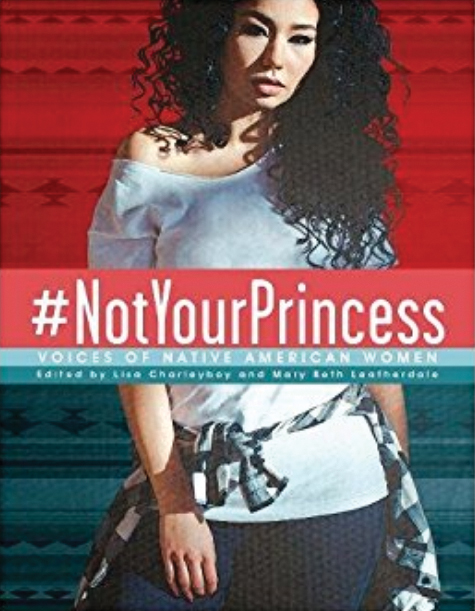

#NotYourPrincess: Voices of Native American Women

by Charleyboy (Editor) and

Leatherdale (Editor)

Annick Press

September 2017

Age Range: 12 and up

Grade Level: 7-12

Paperback: 112 pages

Review by Deborah Locke

Once in a while a girl who is about 14 needs to be reminded that she is strong, she is beautiful, that she will make an important difference in the world, and that she can rise above adversity. You as an adult can tell her that. She may listen.

There’s another way of telling her that.

Leave a copy of #NotYour Princess: Voices of American Indian Women lying around. It will make her – and you – think again about what it means to be an American Indian woman today.

The book, edited by Lisa Charleyboy and Mary Beth Leatherdale, consists of 58 works by American Indian women: essays, poetry, art, history, and graphic illustration. The pieces combine as a whole to address stupid Hollywood stereotypes, addiction, violence, isolation, and courage. What continually surfaces here is the enduring strength of American Indians who are born survivors, who learn the finest parts of their culture and use them to thrive.

Consider this from “The Things We Taught Our Daughters” by Helen Knott (Dane Zaa/Cree):

“Speak up. It is never your fault. No means no. You have the birthright to be free from harm and any man who would violate these treaties between bodies would be dealt with by the women because we protect our own, even if this means calling the police on our own. Because, my girl, you are sacred, valuable, indispensable, and irreplaceable.”

And this by Nahanni Fontaine (Anishinaabe):

When we begin to understand the colonial legacy, and its collateral damage to the minds and bodies of indigenous women, we can begin to forgive, accept, and heal ourselves from the countless hurtful, damaging ways in which this trauma manifests itself. When we embrace our long-standing inner memory of the richness of our teachings, in those moments we reclaim and honor our ancestors’ truth, courage, and resilience.”

See what I mean? Plain truth is the heart of this book, wrapped to appeal to young readers, and that truth matters to older readers, as well. Silly stereotypes about Indian girls as princesses or sex objects or alcoholics crash to the ground. You want to see genuine beauty, the writers ask? Look at Indian women. Photos from classic American movies of white actresses are replaced with photos of American Indian women looking just as glamorous.

Two pages contain photos by Dana Claxton (Hunkpapa Lakota) of a sexualized American Indian woman who through changes of clothes, finally appears in a beautiful, traditional Dakota dress. She’s not wearing a Dakota “costume,” she’s wearing Dakota clothes, and she no longer looks objectified. She looks fabulous.

Humor also makes its way from the pages: graphic artist Winona Linn (Meskwaki) has biting fun with the way Indian girls named Winona – Lakota for “first born daughter” – face a cruel fate in popular culture. Plotlines and poetry often forcibly marry them off to bad news men and ultimately, they throw themselves from cliffs.

“And why are we so fascinated with leaping lovers?” Linn writes. “There are cliffs all over the world from which youth are supposed to have flung themselves…How tiresome. How tiresome to give up like that.”

The story narrator says that she never stood on a ledge for love because it’s not her style. Instead, she’s the first-born daughter of strong-willed parents who has felt doomed at times but remains earth-bound in a country that insists on naming small towns after her. The Winona story ended happily because the People ate well that winter, the Winona heroine had many grandchildren, and the collective winonas of the nation stopped jumping from cliffs.

Some of the truths in the book sting. Indian women who let abusive, violent men off the hook are addressed here. Indian women who retreat must stop retreating, and must dive headfirst into muck and ugliness, wrote Tanaya Winder (Duckwater Shosone). Only then can they recast wounds and return to circles of light, love and courage.

“If you ever need a hero, become one,” wrote Isabella Fillspipe (Oglala Lakota). “If you have something to say, say it.”

Fifty-eight women say a great deal in these 100 pages that you –and your cherished 14-year-old – will turn to often.