By Mark Anthony Rolo

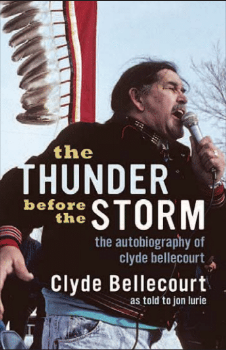

At the start of his fast and furious story, “The Thunder before the Storm: The Autobiography of Clyde Bellecourt,”the famed American Indian Movement leader is quick to point out that while his detractors may dispute historical facts, this is first and foremost the iconic activist’s own story to tell.

Told to long time The Circle journalist,Jon Lurie, Bellecourt is clearly in a rush to tell not only his story, but the story of the American Indian Movement (AIM) from his very inside perspective. And in the light of previous published accounts of the Movement’s beginnings and influence, AIM co-founder Bellecourt’s version greatly helps in bringing this muddled narrative of Indian activism into clearer focus.

In reading Bellecourt’s story, the seeds of activism on behalf of one of the most oppressed groups of people in this country starts with his days of growing upon the White Earth Ojibwe Reservation in northern Minnesota. Bellecourt recognized early on the reality of racism,and that racial violence came in the form of the white man’s religion. In the book, Bellecourt says, “I missed a lot of church, and my hands were beat bloody.They would whack me with the metal side of the ruler and split my knuckles wide open. Of course, I started running away from that, too. If you look at my knuckles today, you’ll see they all have scars on them.”

Bellecourt’s scars have never fully healed. One can easily surmise those scars brought him into the fight for Indian rights and continue to serve as a physical reminder of why he got into that civil fight.

Beginning with the occupation of the abandoned prison isle of Alcatrez in San Francisco in the late 1960s, to the Trail of Broken Treaties to Washington, D.C.,to the long standoff at Wounded Knee at the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota in the early 1970s, Bellecourt was at the heart of each of these storms.He credits his thunderous passion for Indian activism to his days of living on a punitive youth work farm in Red Wing, Minnesota and adult years spent in prison for burglary.

In response to his mother’s concern about his life – getting arrested, beat up and shot – she urged him to focus on the future. Bellecourt said, “Mom, if we ever forget our past we’ll never have a future – our past is our future.”

Before he would become a founding member of AIM Bellecourt found his uture in an elder Anishinabe named Eddie Benton-Banai who was serving time in the same prison as the activist. Benton-Banai became Bellecourt’s spiritual mentor and life-long friend, and would be there to guide him through the challenging efforts to advocate forI ndian people. But even more than that, Benton-Banai taught Bellecourt thepower of the drum. And in page after page of his story, the drum beats loud through the decades of trial and triumph that have defined Bellecourt’s story.

Beyond the very public actions such as occupying Wounded Knee, Bellecourt was fighting a private battle at home in Minneapolis. The call of constant travel to address wrongs against Indians was proving to be a crippling burden on him.For a man so proud of his sacrificial activism, he still harbors one critical heart pain, “The only thing I regret as far as he Movement is concerned is that I didn’t spend enough time with my family, taking care of my children.”

If there is one true hero in this story it is Bellecourt’s wife, Peggy, an Ojibwe woman who has stayed with the activist for more than four decades. To endure celebrity, scandal and the shame of imprisonment of her husband for a cocaine charges, this must be a testament of genuine devotion.And it is in speaking so affectionately about his wife that lends the most sympathy and sincerity to Bellecourt’s storied journey.

Despite his personal demons, Bellecourt is frank in discussing his conviction that the American Indian Movement was plagued with meddling by the Federal Bureau of Investigations. According to the activist, the FBI was at the very least complicit in the death of AIM activist, Anna Mae Aquash, and the conviction of long-time prisoner, Leonard Peltier. To read of conspiracy theories from anyone who was never at the center of Indian activism would be suspect, but Bellecourt’s direct accusations of the feds meddling cannot be portrayed as mere theory.

There will be no doubt that detractors f Bellecourt and the practices of AIM through the years will raise their voices of protest upon reading his story, especially when it comes to Bellecourt’s boast that AIM played a key role in building a Minneapolis urban Indian health clinic, apartment complex, job raining program and a legal defense organization. But those dissenters should remember the activist’s words that begin this tale, “Call me what you want, but I have my own story to tell, and I believe every man deserves the right to tell his story, at least once.” And this activist might be on the mark with that comment. After reading his story one has to give him that much because Creator knows the man has the scars to prove it.