By Winona LaDuke

This is a story of how democracy is supposed to work, and how it does not. This is a story about the future of Minnesota, and if a group of white men and a southern corporation, or a Canadian corporation, can control the future, or if the systems of government, between state, federal and tribal nations will actually work. This is about Minnesota today. It is also a plea for a real multi-cultural democracy, and a respect for Indigenous peoples.

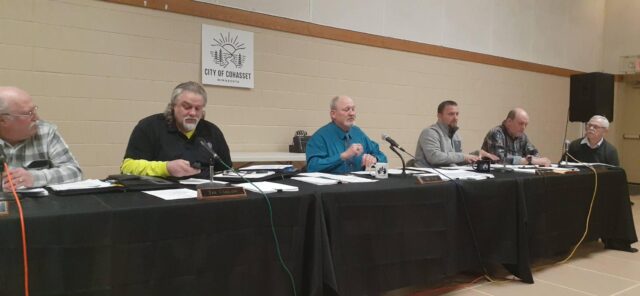

Two pictures tell the story of a system built on racism and destruction:

Here’s how it works in the deep north. A group of white men shut down testimony by all the Native people who have come to a hearing and approve a project, like Kings. That’s what happened in Cohasset recently. In an astonishing display of cronyism and government malfeasance, the Cohasset City Council issued its approval for the Huber OSB Processing facility, hoping to begin construction later this year.

Despite clear state law stating project review should be carried out by state-level agencies without skin in the game and with actual expertise, the Kings of Cohasset claimed Responsible Government Unit (RGU) status for themselves. After they had wined and dined with Huber (the Southern Corporation) and promised $18 million in local and county tax subsidies and direct payments, they turned around and told the public they’d handle the “objective” environmental review.

Proposed to be located in the heart of 1855 Treaty Territory, where seven sovereign Anishinaabe Nations have priority water, hunting, fishing and gathering rights, the Huber facility will impact far more Indigenous people than Cohasset townspeople (approximately 40,000 Anishinaabe people or more live in Northern Minnesota).

The proposed oriented strand board mill will further emaciate the already thin forests of the north, which are now devoid of many of the native species Anishinaabe people have harvested for millenia. The facility will be massive- more than 120 football fields in size, 10 stories tall, and will voraciously consume 400,000 cords of wood annually. To keep costs low and profits high, Huber has said it will cut all of this wood from a 70-100 mile radius (all within 1855 Treaty Territory).

As part of the environmental review process, the City of Cohasset confirmed in writing, several times, that after the period for written comments closed, oral testimony would be taken at a public hearing before a final decision was reached. Turns out, they decided they’d rather have a Huber Huddle pep rally for the Huber corporation instead, complete with matching shirts and hats for hundreds of townspeople. So that’s just what they did.

Without notice to Tribes, indigenous people or other organizations, less than 48 hours before the scheduled public hearing, Huber shut it down. Instead of listening to native people, the Kings gave their people a Huber pep talk, then voted unanimously to approve the project, because, in their expert opinion, it did not have the potential to significantly impact the environment.

Red Lake Nation’s hydrologist, Joshua Jones, came to the public hearing to submit testimony. A trained hydrologist and tribal member, he was deeply concerned about the lack of assessment of impacts to the connected waters in and around the proposed project site as well as impacts to treaty rights.

Many members of Red Lake and White Earth Tribes also have ancestors that lived and were buried on the Leech Lake reservation immediately adjacent to the proposed industrial giant. Joshua, along with representatives from Honor the Earth, the 1855 Treaty Authority, Leech Lake Tribal Government and many tribal members were all denied their previously promised opportunity to testify and put their opposition to the project on record.

Project destruction only begins with massive deforestation, there’s also significant air pollution, endangered species, wild rice, wetland and human health impacts, all of which will directly and negatively affect the Anishinaabe people of Northern Minnesota. Toxic and particulate air emissions known to cause heart and lung diseases and carry a significant risk of premature death will disproportionately impact members of the neighboring Leech Lake and Fond du Lac Tribes living on their tribal reservations.

Honor the Earth’s environmental counsel, Jamie Konopacky, explained that “… it appears that it was only after the City began to fear robust Native testimony that they pulled the plug on the public hearing. Because the written comment period had already closed, and many people had relied on Cohasset’s repeated, written guarantees that there would be opportunity for public testimony, the City deprived a significant number of Tribal Members of their chance to create a public record of Tribal opposition to the Huber project.” What this local government unit did was likely illegal and Honor the Earth and others intend to file an appeal.

If the Huber project really was just a local town project, it is unlikely that thousands of tribal members and allies would cry foul. But this project threatens far more than localized impacts, it disproportionately threatens tribal members and their federally guaranteed treaty rights. In turn, it threatens the very existence of Anishinaabe people who are the original inhabitants of Northern Minnesota. This existential threat is why the Leech Lake Band passed a resolution opposing construction of the Huber Frontier project absent avoidance of negative impacts to treaty rights, forests, wetlands, wildlife, and air quality in 2021.

Lawyers, logging companies, environmentalists, and basically anyone familiar with Minnesota Environmental Review law have no doubt that this project requires full assessment through an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS). Huber was actually clear on this point too, which is why, as a last-minute part of the 2021 budget bill, working with Republican legislators, they snuck through a narrow exemption to one EIS requirement.

The problem is, even with their successful legislative maneuver, the project is so massive and threatens so much harm, that they triggered several other mandatory environmental review requirements. But because their pals at the City of Cohasset claimed RGU status, it turned out those other legal requirements just did not matter.

The Deep North has met the Deep South, and it turns out, unsurprisingly, that the alliance does not bode well for protecting the environment or its original caretakers, the Anishinaabe people, in Northern Minnesota.